Washington in New York -- chs 21, 22 & 23

- Apr 23, 2024

- 24 min read

Updated: May 12, 2024

CHAPTER 21: “THE MOST BITTER AND ANGRY CONTEST"

Thomas Jefferson arrived quietly in New York City on Sunday, February 21, and booked lodging at a tavern on 115 Broadway. The following morning he was sworn in as Secretary of State. That same day Washington’s birthday was celebrated; it’s likely this was the time when Jefferson and Hamilton met for the first time.

As Washington was the father of his country, Jefferson and Hamilton were destined to become the fathers of the two-party system. As to which party each represents in our time is not clear. Being pro-business would seem to make Hamilton a Republican, until one digs deeper into his writings and discover a deep-rooted racial tolerance that would put him in good stead with liberal Democrats. While some historians have framed him as an elitist, Hamilton created a financial system that rewarded ingenuity and hard work rather than class and privilege. Jefferson is harder to pin down. Conservative Republicans and Liberal Democrats alike can quote Jefferson to their own purposes, such was the diversity of ideas he expressed over his long lifetime. The man who drafted the Declaration of Independence and initiated America’s doctrine of separation of church and state, also questioned the intelligence of African Americans, and advocated states’ rights over the power of the federal government. As the nation’s chief executive, however, he expanded the powers of the presidency, and doubled the size of the nation, actions more Hamiltonian than Jeffersonian.

Jefferson and Hamilton were the brightest minds of their generation; after that the similarity ends. As a member of the Virginia gentry, Jefferson was born into a life of ease and privilege. Orphaned at age 11, Hamilton had to work hard for everything he achieved. Both men were voluminous readers, trained in the legal arts, good listeners, and quick on the uptake. Where Hamilton tended to share his ideas freely, Jefferson tended to be reserved and spoke freely only among intimates. Both men could be charming when the occasion called for it. Jefferson avoided conflict; Hamilton welcomed it. Hamilton enjoyed talking about economics, law, and politics; Jefferson favored art, music, science, and architecture. Hamilton was a romantic, obsessed with honor, yet highly pragmatic. Jefferson was an artist at heart who saw the world in terms of good and evil, black and while. Hamilton pursued higher learning to advance his career; Jefferson pursued higher learning for the sheer joy of it.

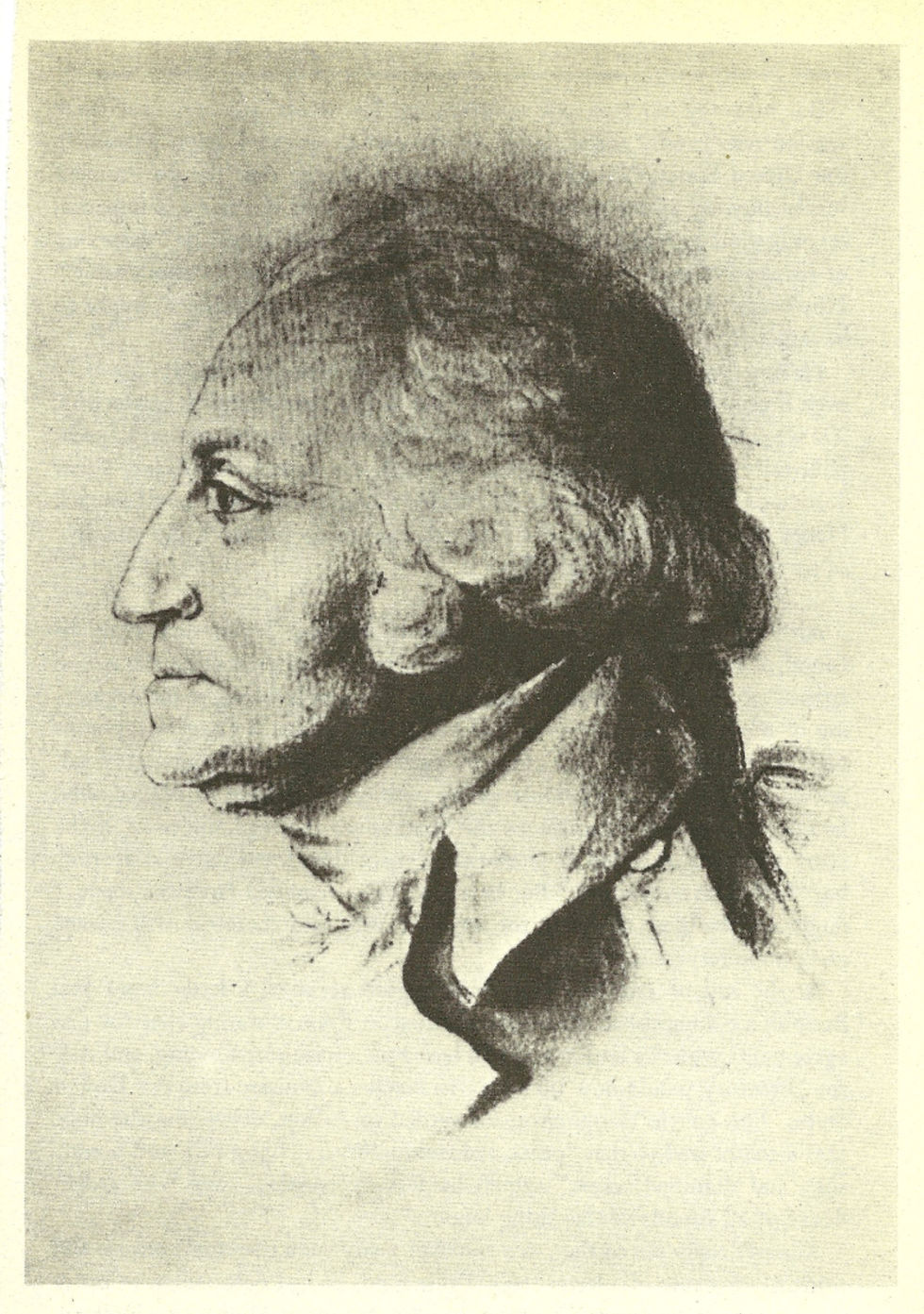

At six-foot-two, Jefferson was unusually tall in an age where the average height was five-foot-seven. He had blue eyes, a long fine nose, a strong jaw, and sandy red hair that he wore tied in a ponytail. On his feet he was square-shouldered and formal in appearance. Sitting he tended to be a sloucher. He bowed to everyone he met, and listened with arms folded across his chest.

Jefferson arrived at mid-point of the First Congress, at the close of the slavery debate and the beginning of the Assumption debate. His first task was to find a suitable house to rent, preferably near the State Department.

MADISON GOES PUBLIC

While Jefferson searched for a house, Madison asked to meet privately with Hamilton. He was going public with his opposition to Assumption, and wanted to pay Hamilton the courtesy of informing him first. By now, Hamilton surely suspected Madison’s change of heart. He recalled later that Madison “alleged in his justification that the very considerable alienation of the debt, subsequent to the period at which he had opposed discrimination, had essentially changed the state of the question.”

In Hamilton’s mind, Madison was turning his back on everything the two of them had stood for, including the role of statesman. Sure, Madison had to face his constituency in next year’s election, but in the best sense of the word, a statesman didn’t worry about elections. He did what was best for his country rather than be swayed by public opinion. Public opinion was fickle. It was motivated by fear and therefore easily manipulated by unscrupulous politicians. At its worst, it was mob rule and quick to trample on individual rights. Madison knew this very well. As the author of the U.S. Constitution, he had designed a government of checks and balances to keep public opinion in check and to protect individual rights. What was Madison doing but giving in to public pressure from back home by opposing Hamilton’s financial plan?

To defeat Assumption, Madison’s strategy was to stall for time, until representatives from North Carolina took their seats in the House. North Carolina was the latest state to join the Union and opposed Assumption. If Madison was to defeat the Assumption bill, he would need North Carolina’s five votes. So he stalled for time. First, he tied up the House for several weeks with debating the merits of discrimination. He hadn’t counted on the slavery debate, but it ate up more time and therefore served his stalling tactics quite well.

Madison’s next move was to divide and conquer. He knew how to count votes, and Funding had the votes. Assumption, on the other hand, was controversial and therefore vulnerable. Madison moved to have the Funding and Assumption Bill separated and debated as separate issues. Hamilton, of course, wanted the two issues debated as one, which is how he saw them. In order for his financial plan to work, he needed the $25 million in states’ debt and what it represented--state creditors made beholden to the federal government. The issues were debated and put to a vote. Despite a number of Congressmen who supported Hamilton, this time the vote went Madison’s way. Funding and Assumption would be debated in the House as separate bills.

With Assumption first on the docket, the focus now was on state accounts--on how much each state owed creditors. On February 24, Madison moved that Assumption be coupled with an "effectual provision" for settling state accounts. After a long debate, Madison's proposal was adopted. A few days later it was moved and approved that the treasury secretary prepare a report on what taxes could be raised to support the state debts if the financial responsibility was assumed by the federal government. Since Hamilton had pointedly avoided this question in his report, many thought the order would either catch him unprepared, or uncover a design to impose highly objectionable taxes. Either way, the result would consume more time and thereby serve Madison’s overall purpose of stalling for time. Hamilton, however, who had been following the debate closely, was prepared. Within two days he presented the House with a report containing ten painless and easily collected sources of taxation, which together would yield more than $1 million annually and thus service the state debts comfortably.

Several weeks of debate followed, as March gave way to April. Debate was particularly rancorous. Jefferson, who sometimes watched from the gallery, categorized the assumption debate as “the most bitter and angry contest ever known in Congress before or since the union of the states.” On April 13, with the five delegates from North Carolina having taken their seats at last, Madison called for the question. A vote was taken and the House defeated assumption by two votes--31 to 29. As Madison knew it would, North Carolina’s five votes made the difference.

Over the next six weeks, as the Funding Bill was hammered into shape, repeated efforts to re-insert Assumption into Hamilton’s financial package, were blocked successfully by the man from Orange County, Virginia.

According to historian Forrest McDonald, Madison’s stalling tactics were a godsend to the very people he detested--speculators. It gave them more time to purchase state securities at mere pennies on the dollar--and southern states securities at that. According to McDonald’s research, during that time eleven New Yorkers purchased North Carolina securities with a face value of $617,185 for a cash outlay of a mere $80,000. Eight other New Yorkers acquired South Carolina securities with a face value of $606,643 for a cash outlay of $120,000. Another twenty-two speculators bought Virginia securities with a face value of $1,070,077 for comparable outlays of cash. Writes McDonald: “Before he was through, Madison would put more profits into the hands of speculators than Hamilton could have done by inviting them to help themselves to the Treasury.”

FRANKLIN EULOGIZED

The same day Assumption was defeated Thomas Jefferson celebrated his 47th birthday. Four days later, on April 17, Benjamin Franklin died. The next day word of his passing reached New York. Flags were flown at half-mast. On April 22, a memorial service was held in the House of Representatives. James Madison delivered the final tribute:

"The House, being informed of the decease of Benjamin Franklin, a citizen whose native genius was not more an ornament to human nature, than his various exertions of it have been precious to science, to freedom, and to his country, do resolve, as mark of the veneration due to his memory, that the 144 members wear the customary badge of mourning for one month."

Historian Joseph J. Ellis writes of the occasion: "The symbolism of the scene was poignant, dramatizing as it did the passing of the prototypical American and (with him) the cause of gradual emancipation. Whether they knew it or not, the badge of mourning the members of the House agreed to wear also bore testimony to the tragic and perhaps intractable (slavery) problem that even the revolutionary generation, with all its extraordinary talent, could neither solve nor face.”

CHAPTER 22: WASHINGTON’S SECOND TRIP (AND SECOND ILLNESS)

George Washington lacked the common touch. Being a man of few words and emotionally distant made him unapproachable. However, a bit of cow dung clinging to the sole of his polished boots could have a transforming effect. On a farm he would open up and talk shop. Touring Long Island the third week of April, that is what he did--talk shop with farmers and be a regular guy.

It was a part of the president’s plan to tour the nation, to see and be seen among the people. Washington wanted to know what the common people thought of the new government; what he was doing was taking an informal opinion poll to find out. At the same time, he wanted to know what was being farmed on Long Island and if there was anything he might learn that could improve the farming methods at Mount Vernon. Being the first planter in Virginia to apply fertilizer to his fields, he was interested to learn that Long Island farmers were using cow dung to fertilize their fields.

WASHINGTON SLEPT HERE

On Tuesday, April 20 Washington set out with his usual entourage of personal secretaries, servants and outriders, in a coach drawn by the usual six white horses. Washington traveled well, but he was a man’s man. On first sight he could make women blush and cause men to stammer. But to have him spending the night in your house? To the average farmer, this was heaven. "The father of our country ate at this table, slept in this bed, and spent the evening talking about MY farm."

Washington’s journal: "About 8 Oclock (having previously sent over my Servants, Horses and Carriage) I crossed to Brooklyn and proceeded to Flat Bush -- thence to Utrich -- thence to Gravesend -- then through Jamaica where we lodged at a Tavern kept by (William) Warne--a pretty good and decent house." While dining at the home of William Barry in Utrecht he complimented Mrs. Barry on her cooking and questioned Mr. Barry about the crops he was growing in his fields. Washington duly noted the types and the yield. "He told me that their average Crop of Oats did not exceed 15 bushls. to the Acre, but of Indian Corn they commonly made from 25 to 30 and often more bushels to the Acre but this was the effect of Dung from New York ... That of Wheat sometimes got 30 bushels and often more of Rye."

The following day, the Washington entourage traveled east to South Hempstead, then southeast to the Old South Road where "we came in view of the Sea & continued to be so the remaining part of the days ride, and as near as the road could run for the small bays, Marshes and guts, into which the tide flows at all times . . . ." Washington took it all in: the weather, the soil, the crop yield. "The Country were more mixed with sand than yesterday, the Soil of inferior quality; Yet with dung wch. all the Corn ground receives the land yields on an average 30 bushels to the Acre. . . . “ Washington spent the second night at Apple Tree Neck farm in Islip, at the house of one Judge Isaac Thompson.

Thursday, April 22, Washington struck out at eight o'clock, traveled east as far as Brookhaven, turned north and crossed over to the north shore of Long Island, passing Coram on the way. "The first five Miles of the Road is too poor to admit Inhabitants or cultivation being a low scrubby Oak, not more than 2 feet high intermixed with small and ill thriven Pines,” writes Washington. “Within two miles of (Coram) there are farms but the land is of an indifferent quality much mixed with Sand. . . . From then to (Setuaket) the Soil improves . . . but it is far from the first quality." Washington spent the third night in Setuaket, at the house of "a Captn. Roe." The Roe house overlooked Long Island Sound.

From Setuaket, Washington turned toward home. "Friday 23d. About 8 Oclock we left Roes, and (fed) the Horses at Smiths Town, at a Widow Blidenbergs . . . thence 15 miles to Huntington where we dined and afterwards proceeded Seven Miles to Oyster-bay, to the House of a Mr. Young . . . where we lodged." Washington noted again that the soil was poor, and the road "a mere bed of white sand, unable to produce trees 25 feet high." As he journeyed west, the soil improved. On the peninsula between Oyster Bay and Huntington Bay, Washington saw what had been an extensive stand of timber that had been reduced to one quarter its original size by the British Army during its occupation of the island in 1776. It was yet another reminder to the general of how fast the cost of war could devour natural resources.

Saturday, April 24. Washington departed at 6 a.m. hoping to reach New York before dusk. According to local lore he stopped at the house of Harry Wilson in Glen Cove and from their porch addressed a group of children. His journal makes no mention of the meeting. In Hempstead, he was served breakfast at the home of Hendrick Onderdonck "where we were kindly received and well entertained. This Gentleman works a Grist & two Paper Mills, the last of which he seems to carry on with Spirit, and to profit...." The paper mill, the president learned, was the first to be built in the state of New York.

From Hempstead, Washington traveled to Flushing, where he dined at noon, and on to Brooklyn, with the sun falling fast on the horizon. "The land I passed over to day is generally very good, but leveller and better as we approached New York. The soil is intermixed with pebble, and towards the West end with other kind of stone which they apply to the purposes of fencing which is not to be seen on the South side of the Island nor towards the Eastern parts of it . . . the Road is very fine, and the Country in a higher State of Cultivation & vegetation of Grass & grain forwarded than any place else I had seen--occasioned in a great degree by the Manure drawn from the City of New York.” Washington beat the sun and arrived home before dark.

Two weeks later, on Sunday May 9, Washington began to feel ill.

WASHINGTON’S SECOND BRUSH WITH DEATH

It would be Washington's last entry in his journal for more than a month. It read simply: "Sunday 9th. Indisposed with a bad cold, and at home all day writing letters on private business." Within 24 hours Washington's cold had turned to pneumonia. He was soon bedridden and having trouble breathing.

Three physicians were summoned. In spite of their efforts, the president grew steadily worse. On Wednesday, May 12, Dr. John Jones, a prominent Philadelphia physician who had attended Benjamin Franklin in his final illness, was summoned to New York. Exactly what he prescribed for Washington is unknown. The president was made as comfortable as possible. Outside the Macomb House straw was laid down to deaden the sound of passing carriages.

Despite every effort to keep Washington's illness as private as possible, word got out--death was imminent. Visitors who called at the Executive Mansion hoping to be admitted to the sickroom were gently turned away by Martha Washington, who sat at his bedside knitting hour after hour. "Called to see the President," representative William Maclay wrote in his diary. He was not let in, but joined the despairing group of politicians and friends in the downstairs parlor, with "every Eye full of Tears his life despaired of."

One of those allowed in to see the President was Thomas Jefferson. He arrived as the president's breathe quickened, shallow respirations grew still fainter. Around four o'clock he saw a change. In a letter to his daughter, Jefferson recounted what happened next: "A copious sweat came on, his expectoration, which had been thin and ichorous, began to assume a well-digested form, his articulation became distinct, and in the course of two hours it was evident he had gone thro' a favorable crisis." This was on May 20. The following morning "total despair" gave way to cautious hope. "Indeed, he is thought quite safe," Jefferson then noted.

Some days later, in a letter to his son-in-law, Jefferson wrote: "You cannot conceive the public alarm on this occasion. It proves how much depends on his life."

While the president kept up a cheerful face for Martha, he admitted to friends, more than he had done as a soldier, that he felt he was dangerously risking his life for his country. "I have already had within less than a year two severe attacks, the last worse than the first," he wrote. "A third will put me to sleep with my fathers. At what distance this may be, I know not. Within the last twelve months I have undergone more and severer sickness than thirty preceding years afflicted me with, put it all together." His physicians, he wrote to Lafayette, advised "more exercise and less applications to business. I cannot, however, avoid persuading myself that it is essential to accomplish whatever I have undertaken (though reluctantly) to the best of my abilities."

GONE FISHING

Although he was able to resume most of his duties by the first of June, Washington did not recover fully for several more weeks. Despite persistent coughing, shortness of breath and chest pains, he felt well enough to take a three-day fishing trip off Sandy Hook. He invited Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton to join him. If they discussed funding and assumption or where to locate the nation’s capital, it went unrecorded. Instead, the president returned with a large haul of sea bass, and much warm praise for his “able coadjutors, who harmonize extremely well together.”

CHAPTER 23: THE SEASON FOR HORSE TRADING

Everything was coming to a head. On June 2, the House passed the Funding Bill and sent it upstairs to the Senate. If the Senate passed funding without Assumption, Assumption was dead. If that happened, Hamilton told friends he would resign his post. What would be the point of continuing? Funding alone would not solve the nation’s woeful economic predicament. If the republic didn’t want to save itself financially, Hamilton wouldn’t be a party to it. Besides, he could make far more money practicing law.

To get what he wanted Hamilton was prepared to do what any self-respecting politician would do--some old-fashioned horse trading.

It was the season for horse-trading. Deals were being discussed nightly over dinner among local and state politicians, congressmen and merchants, on the trading of votes for assumption in exchange for votes on where to place the nation’s capital. Indeed, after all these months, the Residency Bill was still being debated in Congress. Back in January, at the opening of the second session, the House had adopted a new joint rule by which any business left unfinished at the end of one session must begin all over again at the next session, thereby killing the bill that had selected Pennsylvania for the site of the new capital. Now, the site of the capital was up for grabs again. It was a clever bit of political maneuvering engineered by the ever-resourceful James Madison. The man from Orange County, Virginia was prepared to do whatever it took to move the capital to the Potomac.

JEFFERSON HAS A HEADACHE

It seemed everyone was down with some illness in the Spring of 1790. George Washington was incapacitated with yet another near-fatal illness. Madison was waylaid with dysentery. In John Adam's house, everyone but the vice president had the flu. On any given day, any number of Congressmen might be home nursing some ailment. And for all of May Thomas Jefferson was confined to a darkened room with a severe migraine.

Jefferson had a long history of migraine headaches. According to recent studies, his migraines were brought about by work-related stress. Jefferson's latest migraine may have come with the realization that the United States might be pulled apart by one or two regions seceding from the union. Most southern states were threatening to secede should assumption pass, while South Carolina and the northeast states were threatening to secede if assumption wasn’t passed. Despite all the progress that Congress had achieved over the summer of 1789, gridlock had set in and nothing was getting done. Talk of secession was a daily occurrence. There were those advocating that the federal government be dissolved as unworkable, and starting over again.

Having spent four years in France, Jefferson knew the success or failure of the United States largely depended on its credit rating in Europe. The impression that the infant republic was prone to crisis did not exactly inspire confidence abroad. While creditors in Britain, in the Netherlands, and in Switzerland saw massive amounts of interest being earned, they were also seeing danger signals should Congress fail to pass the Assumption Bill. Jefferson knew the mere threat of trouble might be as destructive as the fact itself. Should Europe's bankers fear the worst, they would take action--probably by asking some of the smaller states to liquidate what today would be called "subprime loans." If the states stalled or admitted that they were unable to pay, the bankers might allow partial settlements to be made at a discount, accepting less then full payment in order to get back a portion of their money. The spreading action would develop rapidly to get at least partial repayments from larger borrowers. The result would be the end of easy credit. The effect would further cripple America’s ailing economy.

There was yet another reason for Jefferson to worry. War was impending in Europe. He knew the United States could remain neutral only if it were strong. Strength and good credit went hand-in-hand. As Jefferson put it: "Our business is to have great credit, and to use it little. Whatever enables us to go to war, secures our peace."

Once Jefferson was feeling better he called for a meeting with Robert Morris. Morris was among the most powerful men in the Senate and the prime motivator behind relocating the capital to Pennsylvania. If a deal could be made, he was the one to make it. On June 15, possibly acting on behalf of the president, Jefferson proposed to Morris a compromise: after the present session of Congress ended, the capital would move from New York to Philadelphia, where it would remain for ten years. After that, it would move to a permanent home on the Potomac. The first compromise being agreed to, it was now possible for Jefferson to broker a deal with Hamilton and Madison.

On June 20, Jefferson invited Hamilton and Madison to dine with him at his new quarters at 57 Maiden Lane. It was destined to become the most famous dinner in American history.

DINNER AT JEFFERSON’S

Only one account of the dinner was ever recorded, a couple of years after the fact, by Thomas Jefferson. Here’s what Jefferson wrote:

“Going to the President’s one day I met Hamilton as I approached the door. His look was somber, haggard, and dejected beyond description. Even his dress uncouth and neglected. He asked to speak with me. We stood in the street near the door. He opened the subject of assumption of the state debts, the necessity of it to the general fiscal arrangement and its indispensable necessity toward a preservation of the Union.

“I had not yet undertaken to consider and understand it, that the assumption had struck me in an unfavorable light . . . but that I would resolve what he had urged in my mind. It was a real fact that the Eastern and Southern members (S. Carolina, however, was the former) had got into the most extreme ill humor with one another. . . . On considering the situation of things, I thought the first step towards some conciliation of views would be to bring Mr. Madison and Col. Hamilton to a friendly discussion of the subject. I immediately wrote to each to come and dine with me the next day, mentioned that we should be alone . . . and that I was persuaded that men of sound heads and honest views needed nothing more than mutual understanding to enable them to unite in some measures which might enable us to get along.”

Jefferson’s account of how the meeting took place makes for a nice story but apparently is just that--a nice story. Except for Dumas Malone, Jefferson’s biographer, historians don’t buy it. There are three problems: (1) Hamilton was habitually a sharp dresser and very careful about his appearance; (2) Jefferson would never have been a party to anything he didn’t understand fully. On the very day the deal was made, in fact, he wrote a long letter to James Monroe preparing him for news of precisely the kind of compromise that eventually occurred. Monroe, like most Virginians, opposed assumption. Jefferson assured him that he too found the measure objectionable: “But in the present instance I see the necessity of yielding for this time . . . for the sake of the union, and to save us from the greatest of Calamities”; and (3) at the time Jefferson wrote his account of the deal, he was forming a political party in opposition to Hamilton, and wished to explain his part in the deal, that he had been an innocent participant.

While Jefferson’s account of how the dinner deal came about was a fabrication, in all likelihood the dinner did take place. In 1792 Jefferson told Washington the deal made that evening with Hamilton was the greatest political mistake of his life. “It was unjust,” he said, “and was acquiesced in merely from a fear of disunion, while our government was still in its infant state.”

Historians have debated how many people actually attended the dinner, suggesting that five or more were necessary to make a deal of such a far-reaching consequence. Judging by Jefferson’s account, only three were present. Charles A. Cerami in his book “Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's” makes a compelling case for three being present--Jefferson, Hamilton, and Madison. A woman who often helped with Jefferson's social planning left this account: "When he dined with persons with whom he wished to enjoy a free and unrestricted flow of conversation, the number of persons at the table never exceeded four--each with a dumbwaiter beside him, containing all the utensils and most of the foods needed for the entire dinner. Not only did the intervention of servants disturb the conversation, Jefferson felt, but much of the public discord that often followed was produced by the mutilated and misconstructed repetition of remarks that were heard by servants or by unnecessary guests."

WHAT WAS SERVED

Jefferson had a sophisticated palette, having lived in Paris for four years. He adored French wines, and prior to leaving Paris ordered 288 bottles for shipment to Monticello. His chef, an African-American slave named James Hemings, was trained in the culinary arts while in Paris. Based on accounts of what Jefferson served on social occasions at Monticello, it is possible to reconstruct what may have been served that night in New York. Credit Charles A. Cerami (“Dinner at Mr. Jefferson's”) with the following.

Hamilton and Madison arrived promptly at 4 o'clock (both were known for promptness, and had no patience with those who weren't). A servant led them into the newly appointed drawing room, where Jefferson welcomed them. After being seated, Jefferson served them white wine, which he poured himself. It was one of the esteemed whites, he said, made in the hills near the village of Tains.

Conversation was pleasant. Political discussion before and during dinner was considered strictly taboo.

After half an hour, the three moved to the dining room. There was no prearranged seating at the table, as Jefferson desired an informal atmosphere. Jefferson told his guests to sit where ever they pleased. Two servants appeared and placed a dumbwaiter beside each guest, placed the salad course on the top shelf, and arranged the silverware that would be needed for the entire meal. The dumbwaiters were on four legs, made of walnut, simple, square, fitted with shelves, on which was placed various dishes. Guests could then help themselves without aid of a servant. Because Jefferson preferred white wines to reds, white wine accompanied the salad course. Jefferson described this wine as a 1786 Bordeaux, much esteemed, which he called Carbonnieux. "I had come upon it on a side trip which I had made through the Duchy of Anjou while returning to Paris from a wine-tasting visit to Bordeaux."

In keeping with the Monticello custom, two main courses were served. The first was a capon (a specially prepared chicken) stuffed with Virginia ham and chestnut puree, artichoke bottoms, and truffles, with a bit of cream, white wine, and chicken stock. It was served with a Calvados sauce, made with an apple brandy of Normandy that Jefferson had brought back from his travels. Because the strong flavor of the sauce might overpower a French wine, he served one of his Italian favorites, a Montepulciano from Tuscany.

The second course was the equivalent of the New York boeuf a' la mode, an elegant beef stew that was a favorite at Monticello. James Hemings had improved upon the Monticello recipe by what he had learned in Paris by adding French ingredients that enhanced the flavor. Jefferson served a rare and very expensive red wine from Chambertin.

Various small sweets were then laid out--macaroons, meringues, bell fritters, etc. Dessert itself was something akin to a baked Alaska, ice cream enclosed within a warm pastry. Jefferson then served what looked like a cloudy white wine. It was in fact champagne without the bubbles, called champagne non-mousseux , meaning non-sparkling.

WHAT WAS NEGOTIATED

Having finished desert, negotiations began in earnest. Wrote Jefferson: "I opened the subject, acknowledged that my situation had not permitted me to understand it sufficiently but encouraged them to consider the thing together. They did so.

"After some discussion, which was not prolonged Madison extended his remarks by saying that Assumption was a bitter bill to Virginia and other states that had already paid most of their wartime debts. Hamilton responded by indicating that he understood Virginia's unusual position, but wondered whether a reasonable adjustment of the amount that Virginia would be assessed might enable it to support Assumption? To which Madison responded that such an adjustment would be a step in the right direction, but that considerably more would be needed to soothe the bitter pain that Assumption represented to most of the southern states."

What could be done to sooth the bitter pain that Assumption was causing southerners? For starters, moving the capital from the north to a location on the Potomac. Yes, remove the capital away from the corrupting influence of big cities and northern money-men to a rural setting amidst southern plantations and clean country air. That would do nicely.

Moving the capital south of the Mason-Dixon line "was a just measure," Jefferson concurred in his recounting of the dinner deal "and would probably be a popular one with (the south), and would be a proper one to follow the Assumption. . . . But the removal to the Potomac could not be carried unless Pennsylvania could be engaged in it." Jefferson had Robert Morris's support, which was encouraging, but by itself was not enough. More was needed to insure passage in the Senate. Madison, of course, had the necessary votes to get assumption passed in the House. Did Hamilton have the necessary votes in the Senate to relocate the capital on the Potomac? He assured them he did. Was Hamilton willing to make a trade--assumption for a southern capital?

Yes, he was. The three then toasted the deal.

COMPLETING THE DEAL

In keeping their end of the bargain, Jefferson and Madison would obtain the three or four votes necessary for assumption to be passed in the House. In exchange, Hamilton would help fulfill the terms of Jefferson's compromise deal with Robert Morris. While Morris had already arranged two vote changes that would assure passage of assumption in the Senate, he was having trouble finding the votes necessary to remove the capital from New York. Hamilton must find these votes. He persuaded the only two amenable New Englanders--Massachusetts Senators Tristan Dalton and Caleb Strong. They both strongly favored assumption as the means of rescuing their state from financial collapse. Hamilton convinced them that the only way for assumption to pass was for them to reverse their positions regarding the capital location.

There was something more required of Hamilton, and it had to do with money. As part of the settlement of state accounts, Hamilton arranged to have the sum allotted Virginia under the Assumption Bill increased so that Virginia would end up receiving more than she would be required to pay. The total allotted Virginia ended up being $13 million, or more than half the total of all thirteen states’ combined war debt of $25 million. In Virginia all geese ARE swans.

According to historian Forrest McDonald, the Virginians were "extremely artful" in getting what they wanted. “They used the first trade, which would give the south the permanent capital, to provide a cloak of respectability for the second, which was worth a net to their state of more than $13 million in the final settlement. Thus, because only one trade rather than two appeared to have been made, and because the trading appeared to have involved not money but only assumption in exchange for the capital, they avoided giving the impression of having made a corrupt bargain."

Having negotiated a sweet deal for Virginia, why did Jefferson regret the bargain two years later?

While he understood Hamilton’s plan better than he would ever have admitted, Jefferson did not fully realize the extent of its impact on the nation. The federal government had captured forever the bulk of American taxing power, thus creating an unshakeable foundation for federal over state power. Had Hamilton withheld vital information? Not at all. The Treasury Secretary had explained his views ad-nauseam. According to historian Ron Chernow, Jefferson “had not been duped but outsmarted by Hamilton, who had embedded an enduring political system in the details of the funding and assumption scheme.”

In an unsigned newspaper article published that September, entitled “Address to the Public Creditors,” Hamilton gave away the secret of his statecraft that so infuriated Jefferson: “Whoever considers the nature of our government with discernment will see that though obstacles and delays will frequently stand in the way of the adoption of good measures, yet once adopted, they are likely to be stable and permanent. It will be far more difficult to undo than to do.”

As president, Jefferson would find this to be true as he tried and failed to dismantle Hamilton’s financial system. It was for the best, as Jefferson found out. Later, in making the Louisiana Purchase, he would make the purchase not with the cash (which the federal government didn’t have) but with symbolic money--with government bonds--thanks to the financial system created by Hamilton.

POSTSCRIPT

The deal having been made, all that remained now was for Congress to cast the votes. On June 29 Senators Dalton and Strong changed positions and thereby killed a last-ditch effort to keep the temporary capital in New York City. Two days later the Senate passed the bill putting the temporary capital in Philadelphia and the permanent capital on the Potomac. On July 9 the House approved the Senate bill.

On July 14 the Senate amended the House's Funding Bill by reinserting a provision for Assumption and by changing the interest rates (in order to be in compliance with a revised set of formulas worked out by Hamilton and Robert Morris). On July 22 the House took up the Senate's amendments. Two days later the votes were cast. Various shifts had assumption advocates outnumbered 29 to 33, but on July 24, four Representatives switched votes (with some arm-twisting by Jefferson and Madison) and the measure carried. By July 29, all differences between the House and the Senate bills had been worked out. Having passed Congress, the final bill went to the President for his signature.

Four separate statutes were passed giving life to the proposals Hamilton advocated in “The Report on Public Credit.” One was a Congressional Act for the settlement of state accounts. Another was the Funding and Assumption Act, which provided refinancing and servicing all domestic debts and authorizing a new European loan of $12 million to consolidate and refinance the foreign debt. A third statute provided for the establishment of a Sinking Fund, to insure the public debt was paid off within the prescribed period of 20 years. The fourth act increased and revised import duties along the lines Hamilton had proposed.

The laws as passed were close enough to Hamilton's original proposals to be acceptable to him. Before adjourning on August 12, Congress gave him two new assignments: the House instructed him to make a further report on the public credit, by which it was understood that he would draw up plans for further taxes as well as the creation of a national bank. Hamilton’s new report was to be ready when Congress reconvened in December--in Philadelphia.

The deal that got Hamilton’s financial plan through Congress and landed the nation’s capital in the Upper South, thereby preserving the fragile unity of states, would be forever known as the Compromise of 1790. It was the first of three comprises that would keep the nation united, up to the Civil War. The other two were the Compromise of 1820, and the Missouri Compromise of 1850.

END -

Comments