Washington in New York -- chs 19 & 20

- Apr 20, 2024

- 25 min read

Updated: May 6, 2024

CHAPTER 19: FRANKLIN'S LAST PUBLIC ACT

On his 58th birthday, George Washington supervised the move across town to his new residence, at 39 Broadway.

The president wrote in his journal: "Monday 22nd. Set seriously about removing my furniture to my new house. The two gentlemen of the family had their beds taken there, and would sleep there tonight." (The two gentlemen were Col. David Humphreys and Tobias Lear.)

That same day, Washington received word that the House of Representatives had defeated the Discrimination Bill. It was welcome news.

While the president favored Hamilton's financial plan in its entirety, he did not support it publicly. Washington believed the public did not want a mere politician as president; the public wanted a father-figure, a national leader who operated above the fray and didn’t take sides politically. As commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, Washington learned his job as military leader was part ceremonial and part administrative. The ceremonial part was what the public saw. It was showmanship--pomp and circumstance. As someone who appreciated the theater, Washington viewed the public side of being president as a role to be played, and the role was that of king. He knew this as well as he knew anything. He dressed and acted the part.

A family friend saw him make the transformation once. It was in the middle of informal dinner at the Executive Mansion. Told that some men were waiting outside to express their respect, Washington “disappeared, shortly thereafter making his appearance in full dress.” The “full dress” was his presidential uniform--a dignified blue or black suit, with gold buttons and gold buckles, ceremonial sword, and hat. After exchanging pleasantries, he again retired, changed back into casual clothing and returned to dinner. In the one set of clothes, he was President of the United States, dignified, distant, leader of the nation. In the other, he was General Washington, Virginia gentlemen. Even the press learned to acknowledged the difference.

What the public didn’t see was the administrative side of Washington’s presidency. This was the business side of executive leadership, of setting expectations, of motivating subordinates by whatever means necessary, and of getting results: sometimes unsavory, always necessary. As administrator, Washington used his advisors and his cabinet officers to find solutions, offer alternatives, write his reports and speeches, deal with Congress, keep him well informed, and do his bidding.

Hamilton saw Washington’s role as an aegis, a protective shield, under which the President’s staff worked unfettered, and without which the Treasury Secretary’s financial program very likely would not have gotten off the ground.

The following day, Washington wrote in his journal: "Tuesday 23rd. Few or no visitors at the Levee today, from the idea of my being on the move. After dinner, Mrs. Washington, myself, and children removed, and lodged at our new habitation." The "children" were his step-grandchildren: George Washington Park Custis and Eleanor Park Custis.

Located a block-and-a-half from Bowling Green park, the four-story Macomb House towered over nearby buildings. Like the previous executive mansion at 1 Cherry Street, it was made of honey-colored brick. The house featured a wide entry hall with large, high-ceilinged drawing rooms on either side that were ideal for entertaining and for receiving foreign dignitaries. These rooms had French doors that opened onto a balcony with a breathtaking view of the Hudson River. Washington could be forgiven if sometimes mistaking the far shore for Maryland instead of Jersey.

Washington’s new address was close to everything that mattered. Across the street and down one block was the home of the Supreme Court chief justice John Jay. One block north of the Macomb House were the executive offices of Treasury, State and War. One block up from there, at the corner of Broadway and Wall Street was Trinity Church where the president now attended Sunday service. One block east of Trinity Church, at the corner of Wall and Nassau Street, was Federal Hall. Further east, at the corner of Wall and Water Street, was Merchant’s Coffee House, where each day public securities were being sold in what was a bull market. How long the bull market would last depended largely on what Congress did with the funding and assumption bill.

There was one piece of unfinished business bothering Washington and that was the appointment of Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State. Washington had waited three months for his reply. Finally, on February 14, it arrived in the mail. Jefferson’s letter read in part:

“Sir, I have duly received the (follow-up) letter of 21st January with which you have honored me, and no longer hesitate to undertake the office to which you are pleased to call me. Your desire that I should come as quickly as possible is a sufficient reason for me to postpone every matter of business, however pressing, which admits postponement. Still it will be the close of the ensuing week before I can get away, and then I shall have to go by way of Richmond, which will lengthen my road . . . I hope I shall have the honor of satisfying you that the circumstances which prevent my immediate departure are not under my control.”

JEFFERSON COMES NORTH

Jefferson had planned to return to Paris after Christmas. Being minister to France suited him perfectly. The job consumed little of his time or energy. He had plenty of opportunity to study architecture, to travel to the south of France, and on occasion to get over to London and shop. A voracious reader, he was forever buying books on a wide range of subjects. Indeed, among the many items he had shipped from France was a caseload of books. While in Paris, he developed a taste for French cooking (he sent his personal chef to French culinary school) and especially for French wine.

The position of Secretary of State did not suit him and he knew it. Jefferson feared his time would be consumed with mundane details, he would be at the beck and call of the president, and no longer have time to pursue his many interests. Madison assured him that would not be the case, but for the most part that’s how it turned out to be. Like most creative people, Jefferson was a free spirit and didn’t like being tied to a job. Being highly ambitious, however, he could not resist the allure of being a part of Washington’s inner circle.

In New York, Jefferson would have influence with the president and perhaps be next in line for the nation’s top office. Not so in France. For these reasons, he accepted the appointment as Secretary of State.

Jefferson saw his daughter Martha married to Colonel Thomas Mann Randolph on February 23. On March 1, he boarded his phaeton (a coach with a pulldown top--the sports car of its day) and departed for New York. On the way he stopped in Richmond to obtain a two-thousand dollar loan from his English creditors. Like most Virginia planters, Jefferson was perpetually short of cash. A week later he traveled to Alexandria where he was trapped by eighteen inches of snow. He sent his phaeton on to New York by boat and booked passage on the next stage coach bound for New York. In Philadelphia he stopped to see an old friend--Benjamin Franklin.

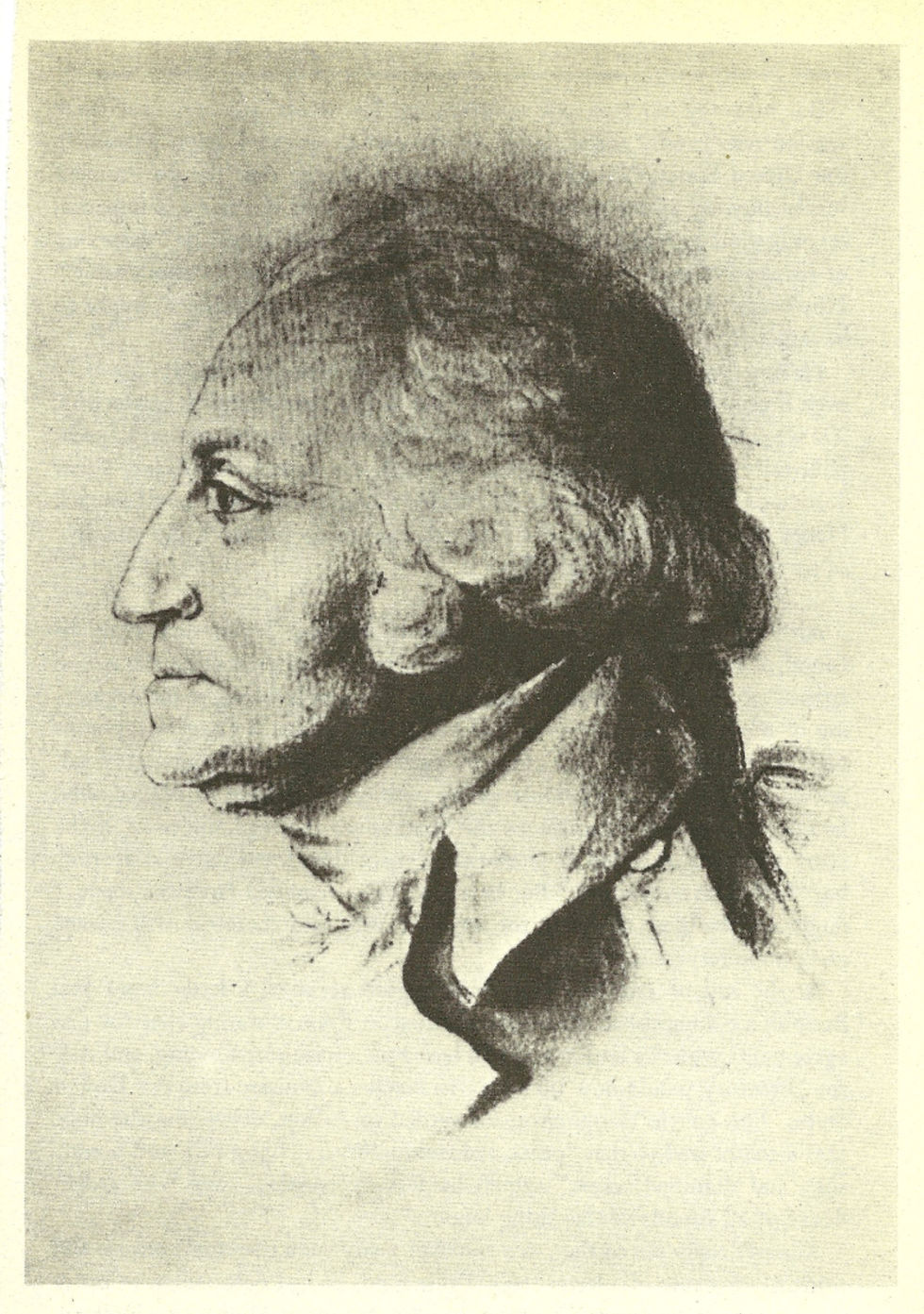

If everyone wanted George Washington as their king, then everyone wanted Ben Franklin as their uncle. Franklin’s bespectacled and wizened eyes tended to ignore people’s vices and to see only their virtues. That did not mean Franklin suffered fools gladly, as we shall see. Like Hamilton, he was an Horatio Alger story come to life, the poor boy who overcame a world of obstacles to rise to the top of society. Franklin was America's premier scientist, humorist, business strategist, journalist, statesman and diplomat. Beloved in France, his visage was instantly recognizable throughout North America and in all of Europe. Of all the Founders, Benjamin Franklin was the person most responsible for making the United States a haven of religious tolerance.

Franklin came late to the patriotic cause. He spent most of the 1760s in London attempting to obtain a royal charter for Pennsylvania. As late as 1771 he lobbied for a position within the English government. When he returned to the colonies, however, he was thoroughly disgusted with the English Parliament's handling of the American crisis. He joined the patriotic cause and rose quickly to the top of political leadership. Franklin was the only person to sign all four of the documents essential to the founding of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty with France, the Peace Accord with Britain, and the Constitution.

Franklin and Jefferson sat on the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson wrote the bulk of the document, with an assist from Franklin and John Adams. A decade later, Jefferson replaced Franklin in Paris as minister to France.

Franklin's contribution to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 was modest. His closing speech, however, helped convince the delegates to set aside their differences and sign the document. Among his closing remarks:

"I agree to this Constitution, with all its faults, if they are such . . . I doubt whether any other convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution; for, when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected?

"It therefore astonishes me, sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear that our councils are confounded, like those of the builders of Babel, and that our states are on the point of separation, only to meet hereafter for the purpose of cutting one another's throats.

"Thus I consent, sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best."

At the time of Jefferson’s visit, Franklin, now age 84, was involved with the final project of his long public life--the abolition of slavery. Bedridden and near death, he’d been following the slavery debate in Congress in the newspapers. While Jefferson was in transit, a great deal had been taking place in the House.

On March 8, the special committee had announced it was ready to give its report.

Representatives from the Deep South protested immediately and vociferously. It was neither the time nor the place to be debating slavery, they said. There were Quakers in the gallery. The press was present. It seemed the whole world was watching--standing in judgement. The debate was not for public consumption. If anything, it should be held in private among gentlemen, as it had been on past occasions.

The delegates from South Carolina were particularly outraged. William Loughton Smith pointed up at the gallery and likened the Quakers to “evil spirits hovering over our heads.” James Jackson made it his duty to glare threateningly at the gallery whenever there was negative reaction. He made no bones about his feelings: Quakers were lunatics, he said, and then launched into a long and mostly incoherent tirade. The best the press could make of it was that any decision by the House to receive the committee report was tantamount to the dissolution of the union. Despite their protests and their threats, the Deep South did not have the votes to stop the committee report from being aired.

REACTION TO THE COMMITTEE REPORT

On March 16, the committee presented its report. Among the key points:

-- Congress had no power to prohibit the slave trade before 1808, and no power to emancipate slaves or to interfere in the states' "internal regulations" of slavery;

-- Congress could, however, regulate the slave trade by levying a ten-dollar importation tax referred to in the Constitution;

-- Congress also could encourage state legislatures to "revise their laws from time to time, when necessary" with regard to the two issues, and promote the ideals listed in the petitions.

The report concluded "that in all cases to which the authority of Congress extends, they will exercise it for the humane objects of the (petitioners), so far as they can be promoted on the principles of justice, humanity, and good policy."

It was mild stuff, but one would never know it judging by the reaction from the Deep South.

Aedanus Burke of South Carolina denounced the Quakers as spies, traitors, and suppliers of the enemy. He became so unruly he had to be called to order.

Cool as always, William Loughton Smith spoke in a softer voice. To accept the report in its present form, he said, "would excite tumults, seditions, and insurrections." Not only that, it would destroy all that slavery had made possible: the southern economy and the southern way of life, a life of culture, refinement, and valor.

These speeches were just the warmup acts for the main event: James Jackson.

Jackson stacked a number of books on his desk, including the Bible. The Bible, he said, sanctions slavery in several passages from the Old Testament. Are not the two precepts, “Masters treat your slaves with kindness: Slaves serve your masters with cheerfulness and fidelity . . .” clear proofs?

The most reliable and recent studies of African tribal culture, he said, demonstrated that slavery was a long-standing custom among Africans themselves. Enslaved Africans in America were simply experiencing a condition that they would otherwise experience, probably under more oppressive conditions, in their native land.

Jackson read selected passages from Thomas Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia. "What is to be done with the slaves when freed?" Jackson read, quoting Jefferson. Either they must be incorporated where they are or they must be colonized somewhere else. The two races cannot live together on equal terms because of "deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites--ten-thousand recollections by the blacks of the injuries they have sustained--new provocations--the real distinctions that nature has made, and many other circumstances which divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which would never end but with the extermination of one or the other race."

"Perhaps there were a few whites in the North who did not concur with Mr. Jefferson's sentiments,” Jackson said. Perhaps the Quaker petitions approved of racial mixing and looked forward to "giving their daughters to negro sons, and receiving the negro daughters for their sons."

Jackson spoke for two hours. After he finished, there was no rebuttal. Not in the House, anyway. A rebuttal would be forthcoming, however, all the way from Philadelphia.

FRANKLIN’S PARODY

Jackson's speech was published in newspapers around the country. From his deathbed in Philadelphia, Franklin read an account of Jackson’s speech in the Federal Gazette around the time of Jefferson’s visit. Whether or not Franklin and Jefferson discussed the House debate is not known. By the time the Virginian arrived in New York, on March 21, Franklin had penned his response. A satire, it appeared in several newspapers from Philadelphia up to Boston but nowhere south of the Potomac. It was Franklin’s last public act.

Wrote Franklin:

"Reading last night in your excellent paper the speech of Mr. Jackson in Congress, against meddling with the affairs of slavery, or attempts to mend the condition of the slaves, it put me in mind of a similar one made by Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim, a member of the Divan of Algiers. . . . It was against the petition of the sect called Erika, or Purists, who prayed for the abolition of piracy and slavery, as being unjust. Mr. Jackson does not quote it: perhaps he has not seen it. If, therefore, some of the reasonings are to be found in his eloquent speech it may only show that men's interests and intellects operate and are operated on with surprisingly similar circumstances."

Using Sidi Mehemet as a stand-in for Jackson, the Devan of Algiers for Congress, and the Erika, or Purists, for the Quakers, Franklin parodied Jackson’s speech in the Algerian speech, which he dreamed up. At the time, Algerian pirates in the Mediterranean were raiding American vessels and making slaves of the captives. Franklin's parody compared the American and Algerian policies and showed there was little to differentiate them. Where Jackson used Christianity to justify enslavement of African-Americans, Sidi Mehemt used Islam to justify enslavement of Christians.

Paraphrasing Jackson, Franklin quoted Sidi Mehemet’s fictitious speech:

If we forbear to make slaves of their people, who, in the hot climate, are to cultivate our lands, who are to perform the common labors of our city, and in our families? Must we not then be our own slaves? And is there not more compassion and more favor due to us Mussulmen, than to these Christian dogs? We have now above 50,000 slaves in and near Algiers. This number, if not kept up by fresh supplies, will soon diminish, and be gradually annihilated. If then we cease taking and plundering the Infidel ships, and making slaves of the seamen and passengers, our lands will become of no value for want of cultivation; the rents of houses in the city will sink one half, and the revenues of government arising from its share of prizes must be totally destroyed."

If the trade and keeping of Christian slaves be abolished "who is to indemnify their masters for the loss? Will the state do it? Is the treasury sufficient? Will the Erika do it? Can they do it. . .? And if we set our slaves free, what is to be done with them . . .? Our people will not pollute themselves by intermarrying with them. . . ."

As slaves "is their condition made worse by their falling into our hands? No . . . they are brought into a land where the sun of Islamism gives forth light, and shines in full splendor, and they have an opportunity of making themselves acquainted with the true doctrine, and thereby saving their immortal souls. . . ." Are not Christians "better off with us, rather than remain in Europe where they would only cut each other's throats in religious wars. . . .? How grossly are (the Erika) mistaken in imagining slavery to be disallowed by the Al Koran! Are not the two precepts, to quote no more, Masters treat your slaves with kindness: Slaves serve your masters with cheerfulness and fidelity, clear proofs to the contrary. . . ?"

Franklin concluded the paraphrase of Jackson’s speech with the Algerian saying: “The Doctrine, that Plundering and Enslaving the Christians is unjust, is at best problematical . . . and . . . that it is in the Interest of the State to continue the Practice; therefore the Petition be rejected.”

The same day Franklin’s letter was published in the Federal Gazette, the House of Representatives did as Jackson requested and rejected the Quaker and Franklin petitions.

CHAPTER 20: THE SLAVERY (Un)RESOLUTION

No shouting, no brawls, no threats of secession. On the floor of the House of Representatives, all was sweetness and nice.

Several northerners who previously had sided with the Quakers expressed regret that the petition to end the slave trade had gotten out of hand. Fisher Ames of Massachusetts wondered why the House had allowed itself to be drawn into such a divisive debate over what he now called "abstract propositions." James Jackson of Georgia was feeling particularly charitable. He thanked Ames and his northern colleagues for “seeing the error of their ways.” He said it was nice to see again the old conciliatory spirit that formerly had united northern and southern interests.

The events in Congress that day, however conciliatory, were among the supreme ironies of the young republic. On the very day Benjamin Franklin’s letter appeared in newspapers making a mockery of James Jackson's justification of slavery--March 23, 1790--the House of Representatives decided to ignore slavery as if it didn’t exist. And it did so without so much as a whimper of opposition from northern abolitionists in Congress.

Obviously, something had happened, some sort of deal worked out between factions, done privately and out of public view. Who could have brokered such a deal? While the answer isn’t known with certainty, evidence points to the man from Orange County, Virginia.

James Madison was personally embarrassed by the slavery debate, embarrassed that it had gotten out of hand, and embarrassed that it was reported in the newspapers. He found the blatantly proslavery arguments of the Deep South "shamefully indecent," and "intemperate beyond all example and even all decorum." While he lived south of the Mason-Dixon Line, he felt more comfortable operating on the high moral ground of the north, where slavery was fading away. As floor leader and a progressive southerner, he was in a unique position to end the rancor by bringing both sides to the table and brokering a compromise.

SEVEN RESOLUTIONS

In the days leading up to the compromise, the subcommittee that had been meeting behind closed doors reported back to the House with Seven Resolutions in response to the Quaker petition. The Deep South did not want the resolutions aired publicly and asked to have the committee’s report tabled. For the moment, Madison agreed. His motive was not merely to table the report--he wanted to render it of none effect. It was at this point that a deal was made that returned unity to the floor.

With a sense of new-found unity--and Madison controlling the outcome--the House went into committee of the whole and addressed the Seven Resolutions. However tepid, the Resolutions were troublesome to slave holders and therefore needed revising. After discussion, the seven resolutions were reduced to three. A proposed tax on the slave trade was dropped altogether, as was the seventh resolution, with its vague declaration of solidarity with the benevolent goals of the Quaker petitioners. The new language of the second resolution read in part: "The Congress have no authority to interfere in the emancipation of slaves, or in the treatment of them within any of the States; it remaining with the several States alone to provide any regulation therein, which humanity and true policy may require." Instead of imposing a moratorium on congressional action against slavery until 1808, as specified in the Constitution, the revised resolutions made it unconstitutional "to attempt to manumit them at any time." In other words, any future effort at emancipation by the federal government was strictly prohibited. Thus, the revised version of the committee’s recommendations were a resolution to do nothing. It passed the House easily.

According to American historian Joseph J. Ellis, the decision that day in the House of Representatives had the equivalent effect of a landmark Supreme Court decision that prohibited any government effort at ending slavery and the slave trade--forever.

In 1792, when another Quaker petition was presented in the House, William L. Smith of South Carolina referred his colleagues to the earlier debate of 1790. The petition was withdrawn. Some 40 years later, in 1833, Daniel Webster cited the same precedent, when he said: "My opinion of the powers of Congress on the subject of slaves and slavery is that Congress has no authority to interfere in the emancipation of slaves. This was resolved by the House in 1790. . . ."

A number of people with the political clout to have made a difference kept silent. Among the seven most influential people in America, only one spoke out--Benjamin Franklin. The other six were George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. While their positions on slavery are similar, their records are remarkably different, as the following illustrates:

GEORGE WASHINGTON

Washington was born at a time when slavery had yet to be questioned anywhere in the colonies. As a young man, he was a tough task master, but as he grew older he began to change. Whippings stopped. He encouraged marriage among slaves, and to keep families together resolved not to sell or trade slaves without their consent. Since consent was rarely given, the General found himself with a growing economic liability--a work force larger than he could employ profitably. The problem was partly due to the high-birth rate among Mount Vernon slaves and partly because he switched from growing tobacco to growing wheat and barley which required fewer workers. Most Virginia planters, when overstocked or in need of quick cash, sold a few slaves. Washington did not.

As commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, Washington spent eight years in the north where slaves were fewer and gradual emancipation was underway. At first, he was shocked to find free blacks serving in his army. As the war dragged on and enlistment fell off, he urged more slaves to be enlisted with the promise of freedom at war’s end. As a result, the Continental Army was the most racially integrated American fighting force until the Vietnam War. Being in the north for so long, Washington began to see the advantage of free labor, manufacturing, and financial credit, and to question the economics of slavery. While in Philadelphia over the winter of 1778-79, he seriously considered selling his slaves and using the proceeds as investment capital.

After the Revolution, Washington returned to life as a Virginia planter intent on making Mount Vernon profitable again. He acknowledged that slavery was evil but he didn’t see a way of running his large plantation without it. One reason slavery was losing its hold in the north was the endless supply of free labor arriving daily at docks in cities like Boston and Philadelphia and especially New York. The only labor force entering the south was enslaved.

Washington decided the best he could manage was to free his own slaves upon his death. To prepare them for freedom, he intended to have them taught to read and write only to discover Virginia had passed a law making it illegal. In private, Washington was increasingly frustrated with the attitude of his fellow Virginians toward slavery. Should the nation divide along north-south lines, Washington told friends he would side with the north.

JAMES MADISON

The man from Orange County, Virginia seemed to be forever in the middle of two opposing political forces. James Madison was both a nationalist and a Virginian, which were about as compatible as cats and dogs.

Over the winter of 1790, Madison was forced to choose, and he chose to side with his home state, which meant turning his back on the nationalist vision he shared with Hamilton, and siding with a narrow states’ rights agenda that included slavery. The decision would prove irrevocable. Madison would go to his grave as a slave owner.

Madison, like Jefferson, Washington, George Mason, and other liberal-minded Virginians, believed slavery was immoral and inconsistent with the ideals of the revolution. In 1783, as Madison was preparing to return home from Philadelphia after living four years in the north, he learned his slave Billey had become “too thoroughly tainted to be fit companion for fellow slaves in Virginia.” The usual practice with slaves who resisted returning to the life of a plantation as a slave, was to ship them off to the West Indies. It was cruelty in the extreme, as West Indian slaves were literary worked to death. Madison could not bring himself to do this. Instead, he sold Billey in Philadelphia, where he would be set free in seven years. In a letter to his father, Madison explained his actions: why should Billey be punished “merely for coveting that liberty for which we have paid the price of so much blood, and have proclaimed so often to be right, and worthy the pursuit, of every human being?”

As with Washington, time in the north changed Madison’s view and he had trouble readjusting to life on a Virginia plantation. The cruelty and injustice of the slave system so affronted him that he studied law and invested in land speculation as a means of earning a living by other means. It didn’t work. He never practiced law and he failed as a land speculator. So Madison returned to elected office. Politics didn’t pay well but for extended periods it did keep him away from the evils of his father’s slave plantation.

In 1785, as a member of the Virginia Assembly, Madison spoke in favor of a bill (drafted by Jefferson) that called for the gradual abolition of slavery. Reaction to the bill was so volatile that Madison gave up all hope of abolishing slavery in his lifetime. To get elected and to have influence in his state, meant being silent on the slavery issue. Madison’s only consolation was to tell himself that eventually slavery would fade away in the south as it was doing in the north. It was wishful thinking.

ALEXANDER HAMILTON

Born an outcast on a tiny Caribbean island, Alexander Hamilton had little trouble identifying with slaves. As a bastard, he couldn’t attend a christian school. When he was nine, his father left never to return, and when he was eleven his mother died. At age twelve, he was put to work in the service of others. Because he had a head for math, he was made a clerk in a counting house (his older brother James was made a carpenter’s apprentice). A life of “grov’ling” (as he put it) was not what he had in mind for himself. He read Plutarch’s “Lives of Noble Grecians and Romans” and dreamed of one day being famous as a nation-founder.

Hamilton saw African slaves arrive daily at the docks in St. Croix, be whipped into submission and be herded like cattle to the sugarcane fields. Many died from the unrelenting heat and intolerable working conditions. Being white, Hamilton knew he had a slim chance of breaking free of a life of drudgery, which he managed to do, while slaves had absolutely no chance of regaining their freedom.

As an officer in Washington’s army, Hamilton advocated the enlistment of African slaves as soldiers with the promise of freedom at war’s end. “I have not the least doubt the (N)egroes will make very excellent soldiers,” he wrote to John Jay. How did he assess their innate abilities? At a time when Jefferson questioned the mental and moral abilities of blacks, and speculated in writing about their inferiority, Hamilton wrote, “For their natural faculties are as good as ours.”

When the war ended, northern abolitionists began pointing out the contradiction of a revolution for freedom fought by a society that tolerated slavery. “It always seemed a most iniquitous scheme to me,” wrote Abigail Adams in a letter to her husband John, “to fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.”

Hamilton never owned slaves, and was among more than thirty New Yorkers who, in January 1785, formed the New York Manumission Society. Paradoxically, many members were themselves slaveholders. They rejected a resolution that Hamilton supported, requiring members to free their slaves. Nonetheless, over the next decade the Society worked to make slavery illegal in New York and to protect free blacks from being illegally taken into slavery.

JOHN JAY

As president of the New York Manumission Society, John Jay advocated gradual emancipation and apparently decided such a policy applied to himself. The few slaves he did own--five in all--were not manumitted until late in his life.

By all accounts, Jay was a benevolent master. To a fellow slaveholder he wrote: “Providence has placed these persons in stations below us. They are servants but they are men; and kindness to inferiors more strongly indicates magnanimity than meanness.” To an antislavery friend in England he wrote that it was “very inconsistent as well as unjust and perhaps impious” for men to “pray and fight for their own freedom” and yet to “keep others in slavery.”

Jay drafted a petition for the Manumission Society arguing for legislation that would prohibit the export of blacks or slaves from New York. “It is well known,” he argued, “that the condition of slaves in this state is far more tolerable and easy than in many other countries” (i.e. southern states). While the Constitutional Convention was meeting in Philadelphia in 1787, he drafted another petition, this time to urge the new federal constitution to prohibit the import of slaves into the country. The timing wasn’t good as delegates already had decided to remain silent on the issue, and the petition was not submitted.

Within a few years of its formation, the New York Manumission Society opened a school for free blacks, and over the next few decades this school and others sponsored by the society educated more than two thousand African Americans. Many of the graduates went on to become leaders of the black community and leaders of the abolition movement. While Jay was governor of New York (1795-1801), the state passed legislation to end slavery which took many years to implement. It wasn’t until 1827 that slaves were given freedom in New York.

JOHN ADAMS

John Adams never owned slaves, nor hired the slaves of others to work his farm, as was sometimes done in New England. Honest John chopped his own wood, planted and harvested his own fields, and rose to prominence as a savvy Boston attorney.

Despite being against “the peculiar institution,” Adams appeared in several slave cases--for the master, never the slave. It was in keeping with his character to represent those with whom he disagreed, if they had a worthy case. He defended the commanding officer of the British regiment that fired on patriots in the Boston Massacre, and got him acquitted.

Adams was sent to Philadelphia to represent Massachusetts as a delegate to the Continental Congress. As a persuasive and indefatigable speaker, he could talk a reluctant Congress into declaring independence from England, but he could not talk southern delegates into giving up their slaves.

In throwing off the yoke of monarchy, the colonists were attempting to create the world anew. Someone needed to explain it. Adams picked a brilliant young southerner with a flair for writing to find the right words. Possessing a “canine appetite” for books, Thomas Jefferson had little trouble finding the words that went to the very heart of the issue:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

And,

“. . . when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for the future security.”

Jefferson’s initial draft included passages that called slavery into question, passages that were struck out by the delegation-at-large. Indeed, the biggest stumbling block to independence was slavery. The south would not compromise. The south would have its slaves without condition, or there would be no revolution.

Adams, like all northern delegates, was not about to let southern slavery jeopardize the larger purpose, which was independence. Yes, Adams was against slavery but going forward he would speak not of abolition but of gradual emancipation. Gradual emancipation was underway in the north and nowhere was that more evident than in Philadelphia, where Congress was meeting. No doubt, such evidence convinced delegates that the same thing would happen south of the Mason-Dixon Line--eventually. Among the next generation of southern leaders, John Calhoun would speak of slavery as “the scaffolding for the south,” support that would be removed, “when the work was done.”

“Gradual emancipation” proved to be magical words that brought unity to the Continental Congress and ultimately independence from England. The very idea of gradual emancipation allowed slave owners north and south to live with their hypocrisy. Not everyone was taken in. In London, Samuel Johnson asked: “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of Negroes?”

THOMAS JEFFERSON

Among the great Congressional orators of 1776, Thomas Jefferson was an anomaly: he was shy and had trouble expressing himself. Adams recalled that “during the whole Time I sat with him in Congress, I never heard him utter three sentences together.” What Jefferson lacked in speaking skills, however, he more than made up in writing skills. When it was time to draft the Declaration of Independence, the choice came down to two people: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Adams was himself an excellent writer but acknowledged that Jefferson was his better, so the task fell to the shy Virginian.

It took Thomas Jefferson two days to write the first draft. John Adams and Benjamin Franklin made a few stylistic changes then the document went before Congress. It was a painful ordeal for Jefferson to sit through as approximately one-fourth of what he had written was crossed out. While he didn’t breathe a word of protest, he lamented the changes for the rest of life. Congress had “mangled” his manuscript.

Jefferson’s preamble with its ringing endorsement of universal equality--the part everyone remembers--was left intact. The cuts were to the part no one remembers: the lengthy bill of indictment against King George III, chief of which was the long passage in which Jefferson blamed the King for slavery and the slave trade. As emphatic a passage as any, it was to have been the climax of all the charges made against the king. The passage was deleted; Jefferson said later, mainly because South Carolina and Georgia objected. While it condemned slavery as evil, Jefferson’s concluding passage stopped short of endorsing outright abolition. Be that as it may, the passage proved controversial and was stricken out. The preamble was allowed to stand, which would become holy scripture for human rights advocates the world over.

While Jefferson was against slavery, like other southern planters he wasn’t prepared to release his slaves from bondage. He was counting on gradual emancipation to somehow solve the problem for him. What no one seems to have considered at the time was the vastly greater number of slaves living in the south as opposed those few in the north, and that the south--particularly the Deep South--was still importing African slaves while the northern workforce was filling its ranks with immigrant European free labor.

Years later, when it was clear that southern slavery was not fading away but spreading into the western territories, Jefferson grew alarmed. In his final years, it awoke him “like a fire bell in the night,” filling him with terror. He believed the two races could not live together in harmony. Once freed, Jefferson believed former slaves would take revenge on their former captives. “We have the wolf by the ears,” he complained, “and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go.”

Jefferson was not a party to the Slavery (Un)Resolution of 1790 but he would have agreed that silence was the only way of preserving the fragile union. As with the other five, he too believed slavery was morally wrong and would eventually die out, so why risk everything they had struggled to achieve over an issue that was doomed anyway?

FINAL WORD

The founders knew well that the slavery question, if left unaddressed, might be the ruin of their beloved republic. Never did they dream, however, that by avoiding the issue they were condemning 600,000 yet unborn citizens to die in a war that one day would bring closure to “the peculiar institution.” By remaining silent that is, in fact, what they were doing.

END -

Comments