Washington in New York -- Chs 4 & 5

- Feb 27, 2024

- 22 min read

Updated: Apr 12, 2024

CHAPTER 4: UNTRODDEN GROUND

It seemed too good to be true.

Alexander Hamilton’s two great passions in life--politics and economics--were headquartered on the same street where he lived--Wall Street. There was Federal Hall where Congress met daily, and one block down was the commercial bank Hamilton founded, New York Bank. It was about a one-minute walk from his townhouse to the front door of either building.

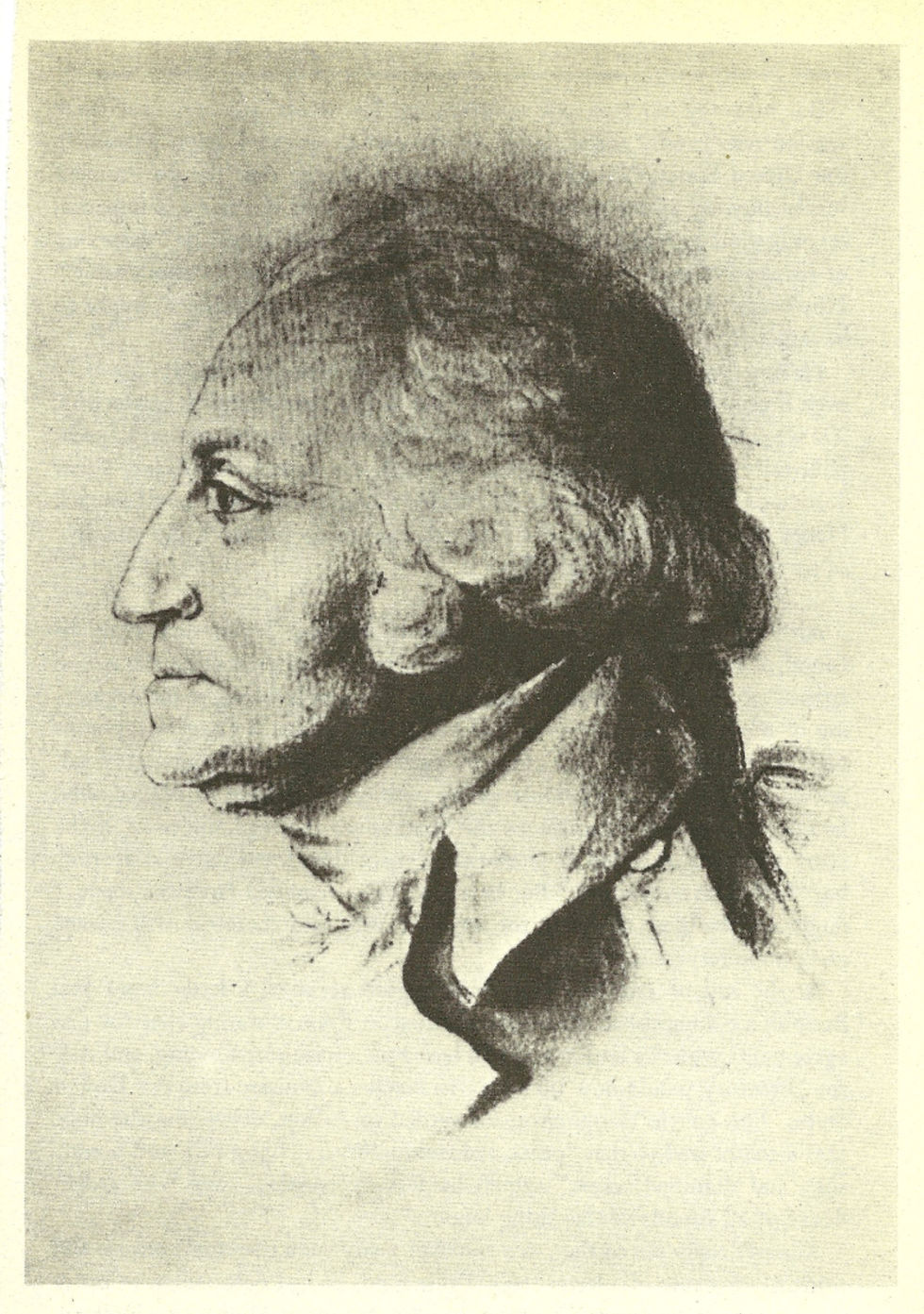

George Washington did not have a place for Hamilton in the new government, but he would. James Madison was having discussions with the President about the creation of the executive departments of state and treasury, and who Washington should appoint to fill them. Both of Madison’s recommended appointees were his friends: Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton.

While Madison and Jefferson were born into the Virginia aristocracy, Hamilton was born on the island of Nevis in the Caribbean, in near poverty. His was a tale right out of Horatio Alger, the poor boy who works hard and rises to middle-class respectability, or, in Hamilton’s case, to upper-class respectability.

Adding further resistance to Hamilton’s climb was that he was born out of wedlock. His father and mother never married. His father disappeared when he was nine and his mother died when he was eleven. His mother taught him how to read, and the books she owned--some 30 in all--constituted his sole inheritance. Not yet a teen, Hamilton went to work clerking for a wealthy merchant on the nearby island of St. Croix. The merchant thought so highly of him that when he became ill and went to New York to recuperate, he put Hamilton in charge of his business. Hamilton was 14 and kept the business running smoothly the four months the merchant away. At 16, Hamilton was sent to America by his Scottish tutor Hugh Knox, a Princeton graduate who was the first to recognize his genius.

Hamilton arrived in New York not exactly a penniless immigrant. He had papers of introduction and what amounted to a college scholarship, thanks to Knox and his deep-pockets friends. There was a problem, however. Before entering college Hamilton would need three years of preparatory school which, when completed, would leave him with just enough money for one year of college. As it turned out, it was more than enough. Hamilton was not only gifted, he was highly motivated. He completed his prep-school studies and passed his exams in one year, and completed his four-years of college in two years. He would have graduated had it not been for the Revolution.

Hamilton sided with the patriot's cause and quit school a month shy of graduation. He took a crash course in trigonometry, learned the art of artillery, and before his twentieth birthday caught the attention of General George Washington. He served on Washington's staff as aid-de-camp for four years. In October 1781, at Yorktown, he led a charge that captured a key redoubt that helped turn the tide on a day that ended in victory for the Continental Army. Horatio Alger never wrote a story quite so bold, and it was only the beginning.

In 1780, while in the army, Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of General Philip Schuyler. The Schuylers were among New York State's most prominant families. If Hamilton was seeking a life of ease, he’d found it. He wasn't. He wanted to pay his own his way. After three months of intensive study of the law in Albany, he was admitted to the bar in July 1783. When the British army evacuated New York city later that fall, he opened his law office at 57 Wall Street.

With the help of John Jay, he formed the New York Manumission Society, dedicated to the gradual emancipation of slavery in New York state. In 1784, he founded the Bank of New York. Today it is the oldest ongoing banking organization in the United States. Working with Jay and others, he helped revive his alma mater, King's College (today’s Columbia College), which had been suspended since the Battle of Long Island in 1776.

Politics was never far from his mind, however. He served as delegate from New York in the Confederation Congress in 1782 and 1783, and resumed his public career by attending the Annapolis Convention as a delegate in 1786. He wrote the call letter for the Constitutional Convention. In Philadelphia he made an impassioned speech for an “energetic” chief executive. He suggested making the presidency a life-time appointment, as with Supreme Court appointments, subject to removal by impeachment. He was not alone in this line of thinking. However, Madison’s Virginia Plan of a cleverly balanced government had by then held sway and carried the day.

Hamilton was not satisfied with the new Constitution, convinced it did not give the Federal Government nearly enough power to succeed. He signed the document anyway and urged others to sign it too. Afterward he co-authored “The Federalist Papers,” eighty-five essays written to rally support for the proposed Constitution. In Poughkeepsie, working in concert with John Jay, he beat overwhelming odds and made New York the eleventh state to ratify the Constitution. Lastly, in a series of letters, he helped convince George Washington to run for president.

On April 30, 1789, from the balcony of his townhouse on Wall Street, Hamilton watched George Washington be sworn in as president. All that remained now was to wait for his appointment as Secretary of the Treasury. Funding the war debt and creating a national bank to use the funded debt as investment capital would, in Hamilton’s mind, further strengthen the federal government and thus insure the success of the young Republic.

New York was Hamilton’s kind of town: fast-paced and money-minded. (Both Madison and Jefferson loathed New York.) In 1789, New York had a population of 33,000 souls, with twenty-two churches, one synagogue, six markets, 4000 houses (many of them boardinghouses), 300 taverns, five newspapers, one college, one public library, one theater, one post office, one bank (Hamilton’s); a debtors’ prison, no hotels, and no hospitals (doctors made house calls and treated patients in their parlors).

As with most eighteenth-century cities, New York was a city of foul smells, especially in the heat of summer. Most streets were dusty in summer and muddy in winter. The streets where the wealthy lived, such as Broadway, White Hall, Barclay, Vesey, Broad, and Wall Street, were paved in bricks or cobblestones, and were tree-lined. New York City was decidedly commercial. People walked fast and talked faster. It was a city of immigrants and the most racially diverse city in America. While a number of wealthy households utilized slaves, the peculiar institution was on the decline and many African-American New Yorkers were free.

WASHINGTON’S MODUS OPERANDI

George Washington did not trust the spoken word. He asked his aids to put their ideas in writing. If Washington had learned anything in his 57 years, it was that he didn’t know everything. He needed the advice of learned men. He needed opinions that conflicted with his own. Don’t tell me what I want to hear; tell me what you think in your gut. That’s how Washington conducted a war; that's how Washington would conduct a presidency: give me your gut opinion, and put it in writing. He’d been in New York only a few days and already he needed advice. The problem: how to get some privacy.

From the moment Washington took possession of the Palace Mansion at 1 Cherry Street, it was overrun with well-wishers, job-seekers, ex-soldiers, and a few people who actually had a reason to see the President. On the first morning Washington was in the house--as he was climbing out of bed--people began to come, and kept coming until he went to bed that night. It was like that every day.

Washington didn’t know what to do. Everything was new. The government was new. The office of president was new. How was the president supposed to act? It was not his house; it belonged to the people. He wanted to be hospitable, but this was too much. Could he ask them to leave?

After several days, when it was obvious the stream of people would not let up, and he could get nothing done, he called in John Adams, James Madison, John Jay and Alexander Hamilton and asked for their advice. This was what was decided: dinners would be held every Thursday afternoon at four, for government officials and their families, by invitation only, in an orderly system of rotation to avoid charges of favoritism. The general public would be invited twice weekly, at a levee for men, on Tuesday afternoons, between three and four, and at a tea for men and women, on Friday evenings. Anyone dressed respectably could attend without invitation. The rest of the time the Executive Mansion would be closed to the public.

Washington felt awkward at these social functions. He was never one of the boys, never a back-slapper, never one with an easy quip, an amusing story to tell, or a tired joke to recycle. His special genius was to operate above the fray, and thus be able to find order in chaos. Being above the political fray would make him one of the nation’s most effective presidents. In social situations, however, such an approach didn’t work. Washington came off as aloof, distant, even arrogant, which he wasn’t.

Washington had another problem: he wasn’t sure how the president ought to act. Somehow, he had to embody the new government’s dignity and authority while at the same time not appear to be kingly. Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay, watching the president at one of these functions, observed: “General George Washington stood on as difficult Ground, as he ever had done in his life.” The tea parties, hosted by Martha, and attended mostly by women, were more to his liking. He enjoyed circulating among the ladies, who tended to swoon over him. Wrote Abigail Adams: “(The President) moved with a grace, and ease that leaves Royal George far behind.”

George Washington did not want to rush into things. This presidency thing was all new. The Constitution didn’t provide a lot of information. The heart of it was Article II, Section 2 and 3, amounting to about 300 words and purposely vague. It would be a matter of learning on the job and, as Washington acknowledged in letters he wrote at the time, setting a precedent for future presidents. He wanted to get it right.

“I walk on untrodden ground,” Washington wrote in a letter to family friend Catherine Macaulay Graham. “There is scarcely any action, whose motives may not be subject to a double interpretation. There is scarcely any part of my conduct which may not hereafter be drawn into precedent. Under such a view of the duties inherent to my arduous office, I could not but feel a diffidence in myself on the one hand; and an anxiety for the Community that every arrangement should be made in the best possible manner on the other.”

Satisfied with the house at 1 Cherry Street, Washington sent for his wife, Martha. At some point, perhaps in the first month, Washington decided to keep his residence and his administrative offices under one roof. The Palace Mansion was large enough to accommodate both. The first floor had rooms suitable for receiving state officials and foreign dignitaries, as well as rooms for his office and those of his personal secretaries and staff.

The second floor had plenty of bedrooms for his family and his two personal secretaries, Tobias Lear and Col. David Humphreys. The third floor served as sleeping quarters for live-in servants. Until Congress created the executive departments, Washington would continue with two holdovers from the old government: John Jay, as Superintendent of Foreign Affairs, and General Hugh Knox, as Superintendent of War. These two and their staffs would continue their work in offices above the Fraunces Tavern.

Washington spent much of his first month in office involved with social activities. He attended the Inaugural Ball, held at the Delancey House on Broadway, on May 7. It was a chance for George Washington to show New York society that their president was a first-class performer on the dance floor. Women waited in line for a turn with the elegant gentleman from Virginia. Abigail Adams “gushed like a school girl” at seeing him for the first time.

From May 10 to May 23, Washington made a personal call on every member of Congress. Who were these men who comprised the First Congress of the United States? They were lawyers, merchants, and wealthy land owners. More than half fought in the Revolution. Nearly all had served as state legislators, delegates in Congress, or delegates to the Constitutional Convention. They were men of impressive bearing and fine oratory skills, accustomed to being at the controls of power. Some were hotheads; most were steady, practical men of reason. Many wore wigs. All knew how to dress. Some brought a valet. Washington’s call on these men was mostly symbolic--and brief. Senator Maclay observed in his journal that the President arrived at his boardinghouse on horseback, dismounted, said good-day, made two “complaisant Bows,” mounted his horse and rode off.

George Washington was a man of few words.

THE SENATE CALLS ON THE PRESIDENT

In keeping with British, colonial and state practice of the legislature issuing a reply to executive speeches, on May 18th the Senate called on the Palace Mansion to issue a formal reply to the President’s Inaugural Address.

Charlie Chaplin could not have made it more amusing.

After knocking on the door, John Adams and eighteen Senators filed into the levee room and were greeted by Washington and two aids, presumably Lear and Humphreys. After nervous bows and clearing of throats, Adams removed a written speech from his pocket but could not read it because he could not keep his hands from shaking. What to do? He placed the manuscript in his hat and, holding the hat with both hands, read the speech, occasionally pausing to turn the page.

It doesn’t stop there.

Washington then removed his written reply from his pocket with his right hand but could not read it without his glasses. He couldn’t remove his glasses from the case because in his left hand he was holding his hat. For an awkward moment he looked at the paper in his right, his hat in his left hand, and his glasses case on the counter, wondering what to do. After shifting some items, he put his hat under his left arm and the paper in his left hand, and with his right hand removed the glasses from the case. He put his glasses on his nose only to be still holding the glasses case. After another awkward moment looking around the room, he placed the glasses case on the chimney mantle. That done, he adjusted his spectacles and read the reply without emotion. The President then invited everyone to sit down. Adams, however, was wearing a sword and having difficulty. Thus, he remained standing and, not knowing what to do, bowed and departed. The Senators rose and one-by-one bowed and followed him out. The meeting, presumably, was then over.

THE FOURTEEN-MILES ROUND

The Palace Mansion was not the Mount Vernon mansion house, and Manhattan was not the Mount Vernon plantation, but there were similarities. At Mount Vernon, partly as an escape from the always-present visitors, but mostly to oversee management of five farms, Washington rode circuit most days, except on Sundays, a journey of about 20 miles. The Mount Vernon plantation ran parallel to the Potomac River for about ten miles and at its widest point penetrated inland about four miles. In New York, Washington continued riding circuit--around Manhattan.

Manhattan was roughly similar in size, being twelve miles long and at its widest about two-miles across. With the exception of New York city, which occupied the southern tip, Manhattan was mostly farmland and therefore was familiar territory to George Washington. There were two crucial differences however: in whatever direction Washington rode, if he rode far enough, he encountered water, as Manhattan was an island. Also unlike Mount Vernon, he didn’t own it. The farms he passed were not his and the farmers and their families were free and white. The President would occasionally stop and “talk shop” with farmers along the way. He enjoyed himself. He needed to get away from time to time and “The Fourteen Miles Round,” as the locals called it, met that need.

As president, Washington would find a much larger circuit to ride--around the entire nation. Beginning with New England in 1789 he would travel as far north as Portsmouth, Maine. Two years later, he would travel as far south as Savannah, Georgia. What was the United States in its early years but a larger version of Mount Vernon? It stretched along the East Coast for a distance of about 1200 miles, and inland about 400 miles. In place of the five farms were five regions. There was (1) the rice producing low country of South Carolina and Georgia, (2) the tobacco belt extending from middle South Carolina through North Carolina, Virginia and much of Maryland, (3) west of the tobacco belt and extending northwest to central Pennsylvania was the frontier country where corn was the cash crop, (4) in the east, north of the tobacco belt, was the wheat belt, extending from Mount Vernon to the middle reaches of the Hudson Valley, and (5) was all of New England, where lumber and fishing were the principle industries.

As with Mount Vernon in 1789, the nation was operating in the red. Before Washington would leave office eight years later, both would be in the black.

CHAPTER 5: MASTER OF THE HOUSE

Who was the man dressed in black speaking from the floor of the House of Representatives in a voice not much louder than a whisper? People in the overhead gallery had trouble hearing him. Expecting to be entertained with heated arguments and shouting matches--which on occasion they were--they threw nuts at him and cried, "Hey, you down there, speak up. We can’t hear you.”

Some men enter a room and make it feel small; such is their magnetism. Short, stoop-shouldered James Madison entered the cavernous House Chamber and made it feel larger than it was. What mattered was Madison was in control. House speaker Frederick Muhlenberg presided, but as anyone in the gallery soon realized, the gentleman with the low-wattage delivery was Master of the House.

Next to George Washington, James Madison was the most influential man in the country. How could it be? The Virginian was not a signer of the Declaration of Independence, nor was he a war hero. Outside of Virginia he was little known. But in the elite world of eighteenth-century American politics, where everyone knew everyone else, James Madison was the ultimate insider.

When Madison spoke--however softly--people paid attention. Madison's mastery of the facts was peerless, due in no small part to his willingness to continue working late into the night while others had gone home to bed. He would never think of entering upon a question of policy or law without first making a thorough investigation of the issues, which meant he would know twice as much as anyone else. As a result, Madison commanded the meeting, whether it was the Virginia legislature, the Constitutional Convention, or the House of Representatives.

Alexander Hamilton was as formidable--with economics. Both men were ambitious in the extreme. With Hamilton, brimming with self confidence, his ambition was obvious. With Madison, shy and self-effacing, his ambition was subtle and not at first obvious. Hamilton looked like what he was--a New York attorney. Madison looked like a care-worn school teacher. Both were bookish, and could quote from the writings of David Hume and Adam Smith, among others. Hamilton leavened his ideology with the pragmatism of a businessman. Madison, never having held down a job, did not possess the experience of the work-a-day world that otherwise might have tempered his idealism. This was the extent of difference between Hamilton and Madison, and eventually it would drive them apart.

For three years the Hamilton-Madison juggernaut worked its magic, elevating the national government into the supreme law of the land while relegating the states to a subordinate role. Now, in the second month of the new federal government, a crack appeared in the Hamilton-Madison collaboration. It began April 8, two days after Washington’s election. James Madison stood up in the House of Representatives and proposed that the 1783 Tariff Bill be enacted immediately. Had Madison stopped there, the Bill would have passed the House before word reached Washington that he was elected president. What held up the Bill was Madison’s addendum, a discriminatory tax against British imports designed to hurt England in the pocketbook. The problem was it would hurt American business in the pocketbook much more.

CREATING A FEDERAL REVENUE STREAM

If the new national government was going to succeed, a federal revenue stream was needed to pay the bills. A tariff bill would serve that purpose.

The principle failure of Congress under the Articles of Confederation was its inability to pass the 1783 Tariff Bill. Under the old government, passage required a unanimous vote. Under the new Constitution, that was not the case; a two-thirds vote of approval in both houses was all that was required. Madison dusted off the 1783 Tariff Bill and attached an addendum for tonnage duties that went beyond revenue into the thorny realm of ideology. Congressmen from Georgia and South Carolina fearing it would hurt the business of their states objected so strongly that it was decided to shelve debate until after the president’s inauguration.

Madison’s Tariff Bill was in three parts: Parts One and Two were holdovers from the 1783 Tariff Bill; Part Three was Madison’s addendum. Part One was an ad valorem tax of five percent on all imports. Part Two contained a short list of enumerated articles (rum, wine, tea, molasses, and the like), to be taxed by duties of a specified amount. This would make the tariff mildly protective, in that business interests with a reasonable claim to protection would receive at least a token of protection, consistent with the government's claim to revenue. Part Three was Madison’s addendum that all goods entering the country be taxed according to tonnage, and that such taxes be levied on three types of vessels:

First type, American-owned vessels, that would pay the lowest duties.

Second type, foreign vessels of which the United States had commercial treaties, that would pay a somewhat higher duty.

Third type, foreign vessels of which the United States did NOT have commercial treaties, that would pay the highest duties of all. Therein lay the problem: the United States did not have a commercial treaty with its biggest trading partner, Great Britain. It did, however, have a commercial treaty with its war-time ally France. In effect, Madison was proposing a tax that favored France and discriminated against England. This was somewhat understandable. France had been an American ally during the Revolutionary War and Great Britain had been the enemy. Madison’s reasoning, however, ignored an indisputable business fact: Great Britain needed American goods (and vice-versa) and France did not.

Nearly all government income from customs duties was from English imports, and eighty percent of all American exports went to England. What Madison’s tariff amounted to was wishful thinking. His discriminatory tax would limit trade with America's most lucrative trading partner and attempt to replace it with a nation that had no need and no desire for American goods. England was a trading nation that valued American goods. France was not a trading nation; what trade it did have was with continental nations--with Italy, Spain, and Germany. England could take its business elsewhere, but what of America? Who was going to buy American goods in the quantity England bought them? To Alexander Hamilton--and to anyone with a head for business--Madison’s Tariff Bill was a textbook example of cutting off the head of the goose that laid the golden egg.

The question is, Why? Why would Madison turn a blind eye to American business interests and propose a bill that discriminated against Great Britain?

VIRGINIA WRIT LARGE

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson shared an image of what America should be, and it looked like Virginia. It was a land without the filth and corruption of cities, without stock brokers and bankers or immigrant labor, a land of vast plantations and plentiful forests, of stately homes and Sunday socials, with the Blue Ridge Mountains as a backdrop and the James River running through it. It was where both the wealthy plantation owner and the small farmer lived in harmony. Such a place, however, was more illusion than reality. However grand and well-ordered they appeared to be, plantations were prison-houses for slave labor, and the small farmer barely eked out a living.

Despite employing slave labor, Virginia planters were up to their ears in debt. To whom did they owe so much money? To British merchants who purchased their tobacco. Thomas Jefferson was an example. His fortune literally rose and fell on the balance sheet of a London counting house. As with most Virginia planters, Jefferson never quite understood why tobacco prices at the commodities exchange would be up one day and down the next, or why his annual yield would net one amount one year, and quite a different amount the next. His very livelihood depended on the numbers entered in the ledger of the British agent with whom he met annually.

Under such a system, wealth was locked up in land. Jefferson, like so many Virginia planters, was land rich and cash poor. He wasn't paid for his tobacco in specie. He was issued credit by which he could purchase English goods from a catalogue--clothes, furniture, fine china, silverware, even the French wines he relished. With his expensive tastes, Jefferson often spent more than he took in. Watching his plantation slip further and further into the red, he at first suspected--and then became convinced--that he was being duped by unscrupulous money men. So did most Virginia planters, including George Washington. However, Washington diversified--switched from tobacco to growing wheat and barley--and broke free. Jefferson merely fell deeper in debt.

It seemed to a majority of Virginia’s planting class that America had won political freedom from Great Britain only to find it was an economic captive.

Madison offered several reasons for discriminating against British trade that revealed his ignorance of America’s business climate: (1) trade with Great Britain was "artificial" and gave that country "a much greater proportion of our trade than she is naturally entitled to" (2) Britain needed American trade more than America needed hers; (3) most of the manufactured goods being imported from England would soon be produced in the United States, and (4) American commerce was highly favored by the French, and with some encouragement (i.e. lower tonnage rates) France would become the United States' most valued trading partner

Meanwhile, across an ocean, Thomas Jefferson was doing his best to make France see the light and become the United States’ number-one trading partner.

JEFFERSON SPEAKS FRENCH AND BUYS ENGLISH

Sent to Europe in 1784, Thomas Jefferson hoped to create a series of commercial treaties with various European nations that would lead to a true free-trade community and, he hoped, would bring an end to England's trade monopoly with the United States. However noble an idea, it had absolutely no basis in reality. Most countries were either indifferent or did not have colonial possessions. None was willing to grant special privileges beyond that of "most favored nation" status, which in eighteenth-century Europe was worth little more than the paper on which it was written.

Having replaced Benjamin Franklin as Minister to France in 1785, Jefferson opened talks along similar lines with various French Ministers. For the most part, they were quite agreeable to Jefferson's proposal, but woefully out of touch with the business needs of their own country. French merchants had little interest in American goods, other than tobacco. In turn, American merchants had little interest in French goods, other than French wine. Whatever American merchants needed was readily available in England. Thanks to the most advanced manufacturing techniques in all of Europe, English products were better made, in greater supply, and cheaper to buy.

Whether he would admit it or not, Jefferson knew this to be true. Having searched all over Paris for a new high-efficiency oil lamp, he found exactly what he was looking for in London. On another occasion, he had to apologize to a French friend for buying an English harness. Said Jefferson sheepishly:

"The reason for my importing (a harness) from England is a very obvious one. They are plated, and plated harness is not made at all in France. . . . It is not from a love of the English but a love of myself that I sometimes find myself obliged to buy their manufacture." It would seem Jefferson wanted Americans to buy expensive and inferior French goods, while he himself was free to purchase cheaper and better-made English goods.

The British economy was dependent on overseas trade, while the French were at best reluctant traders. French merchants were more content with protecting and stabilizing what limited trade they had than in reaching out for new markets to exploit. Despite Jefferson's best efforts, between 1784 and 1790, French imports amounted to no more than one-twentieth of British imports.

The underlying issue was not trade but resentment against England. In the immediate post-war years resentment was understandably high. It grew worse when England reimposed the Navigation Act, which prohibited American trade with the British West Indies. Alexander Hamilton and John Adams spoke of retaliation. The correspondence of Jefferson and Madison during this time reek with hatred of all things English.

As years passed and the American economy picked up, resentment lessened. Given London’s easy credit it was highly beneficial to be doing business with England. At the same time, American merchants were finding new markets for their goods, in Russian ports on the Baltic, even in far away China. As important, the British West Indies, closed as it was to American trade, was in fact remarkably accessible to enterprising American shippers. By 1789, hatred of England was still given voice, but with less conviction. Among American merchants from Boston all the way to Savannah, Britain was no longer viewed as the enemy, but as a business partner. Finally, there was no escaping the fact that nearly all government income was generated from taxes on English goods entering the country. Madison chose to ignore these facts, and under his influence, so did the House of Representatives.

MADISON’S MASTERY DOES NOT EXTEND TO THE SENATE

Since April 8, when Madison introduced the tariff bill, opposition to the tonnage discrimination clause gradually faded. In May, after two days of debate, the House passed the bill and sent it upstairs to the Senate for confirmation.

Occupied with business of its own, the Senate did not act on Madison’s Tariff Bill immediately, thus allowing opposition time to make its case. Senate record keeping in 1789 was dismal at best so there is no record of what actually transpired when the Senate debated Madison's discriminatory clause. From letters and journal entries, however, it seems clear that city merchants did a fair amount of lobbying, probably at Alexander Hamilton's directing. Whether or not James Madison knew that Hamilton was in fact working against him is not known. They continued to be on good speaking terms. That summer, a woman remembered seeing them together "turn and laugh and play with a monkey that was climbing in a neighbor's yard."

When the Senate voted the decision was nearly unanimous--in opposition to the bill. Such a policy as Madison’s, argued the Senate, would only lead to needless and ruinous commercial warfare, and Great Britain had far greater capacity to injure America economically than America to injure her. It sent the tariff bill back to the House minus the discrimination clause. Twice the House returned the bill to the Senate with Madison’s clause reinserted, and twice more the Senate rejected it.

At some point, the Tariff Bill was divided into two bills--a tariff bill (basically the 1783 Tariff Bill), and a tonnage bill, to be debated and voted on as separate issues. Thus separated, the Tariff Bill was approved by both houses without further debate. Washington signed the Tariff Act into law on July 4. The House eventually relented and passed the Tonnage Bill minus Madison’s discriminatory clause. The Tonnage Act was signed into law on September 17, 1789.

THE TARIFF ACT AND ITS AFTERMATH

Madison, normally the conciliator, took the result in stubborn bad grace, characterizing the opposition as "chiefly abetted by the spirit of this City, which is steeped in Anglicism." Massachusetts Senator Fisher Ames wrote in his journal: "The Senate . . . as if designated by Providence to keep rash and frolicsome brats out of the fire, have demolished the absurd, impolite, mad discrimination of foreigners in alliance from other foreigners."

The Tariff Act and the Tonnage Act raised the necessary revenue to fund the federal government, but who was going to collect it? That was determined by two additional bills--The Collection Act, and the Coast Act, passed in Congress and signed into law in 1789.

The Collection Act established a number of collection districts, each with a port of entry at which resided a number of federal officials, including a collector, a naval officer, and a surveyor. Other ports in the district were designated as ports of delivery only, and all ships bound from them had to stop first at the port of entry to declare its cargo and pay the federal duties. Revenue officers had powers of search and seizure and to enact penalties for violations. A revision in 1790 established the United States Coast Guard, that included the construction of 100 cutter ships used as enforcement.

The Coast Act of 1789 established federal forms for registering and clearing all vessels plying American coastal waters and regulated the domestic, undutied trade among the states up and down the Atlantic Coast.

With the Lighthouses Act of 1789 the federal government assumed control of all lighthouses, beacons, and buoys which previously had been the domain of the states.

These newly created federal departments would employee 500 people who in turn would report directly to the newly created Treasury Department.

Hamilton remained Madison’s choice for Secretary of the Treasury, but the day was not distant when the Virginian would turn on his friend.

END -

Comments