Mr. Jefferson Builds His Dream House

- richardnisley

- Sep 16, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 21, 2025

It was not the Monticello we know today. The house Thomas Jefferson returned to in 1789--after four years in France--was not that much different from other Virginia plantation homes. It was impressively large and left little doubt in the minds of visitors that here lived a country gentleman of wealth and taste. What set the house apart from other plantation homes were the double porticoes--one order of Greek-style columns stacked on top of another. The lower level consisted of four Doric columns while the upper level consisted of four Ionic columns. Jefferson had copied this double portico motif from Andrea Palladio's last word on architecture, "The Four Books of Architecture." Andrea Palladio was the Frank Lloyd Wright of his day, only bigger. He was and is the most imitated architect in history, and in America Thomas Jefferson was his biggest fan.

Before unpacking his bags, Jefferson walked around the exterior of his house and noted signs of neglect during his long absence: flaking paint, warped panels, and the still-unfinished porticos. A few weeks of carpentry work and a fresh coat of paint and the house would be perfect. Instead, Jefferson decided much of the house would have to come down. He had a new design in mind. His European experience had given him an opportunity to see firsthand several of the most stylish examples of Palladianism architecture as interpreted by the French. One residence in particular caught his attention: the Hotel de Salm in Paris, a wide rectangular building with a central, semicircular columned bay that was capped with a dome. When Jefferson sat down at the drawing board to redesign Monticello, the image of the Hotel de Salm with its intriguing dome was foremost in his imagination.

Those who knew Jefferson well believed that Monticello would never be finished. It would always be a work in progress and therefore subject to change, depending on Jefferson's latest architectural whim. Work originally began in 1768 with the clearing of a mountaintop near the Jefferson family home. The decision to build his dream house atop a 867-foot mountain rather than beside a broad river set Jefferson apart from other Virginia planters and added significantly to building difficulties.

Rivers were the lifeblood of Virginia. Rivers joined the interior regions to the Tidewater, and to the world. The Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James Rivers allowed Virginia's chief commercial product, tobacco, to be transported with relative ease from the inland counties to the shipping ports on the Chesapeake. It was along these rivers that the great plantation manor houses were built. Rivers made it easy to transport building materials, furniture, and supplies. Deciding to build his house atop a mountain meant that lumber, bricks, doors, windows, furniture, Jefferson's voluminous library, as well as drinking water, would have to be hauled up to the mountaintop. Why go to all the trouble? To enjoy the view from the top, of course. It was a case of putting aesthetics ahead of practicality.

Most substantial plantation homes were built by skilled craftsmen. Usually, a master bricklayer or carpenter assumed the role of what today would be a general contractor: he would hire and supervise other carpenters, sawyers, joiners, bricklayers, plasterers and painters. Slaves did the grunt work: the digging, the hauling, the heavy lifting. Architectural designs were either copied from existing houses or selected from pattern books and modified to meet the owner's requirements. Jefferson not only designed his own home, he acted as his own general contractor. He insisted on paying as he went in order to keep from going deeper in debt. Money often ran out and Jefferson was away a lot.

As a result, work proceeded at irregular intervals. Sixteen years passed when he departed for France in 1784, and still his Monticello dream house was not finished. Upon his return in 1789, he intended to tear down much that was finished and start over again. It must have seemed like madness to his neighbors, but to Jefferson it made perfect sense. He wasn't building a house; he was creating art. Nowhere was this more evident than with the dome. Other than providing an elegant cap for a stylish Palladian residence, the dome had no real purpose. Building it would stretch the capabilities of his skilled craftsmen to the absolute limit. No doubt they learned as they built, tearing down and rebuilding until they got it right. When it was finished, the dome room, or "sky room" as it was sometimes called, was used as a children's playroom, a spare bedroom, and finally as a storeroom. Other than that, Jefferson had no real purpose for the space beneath the dome.

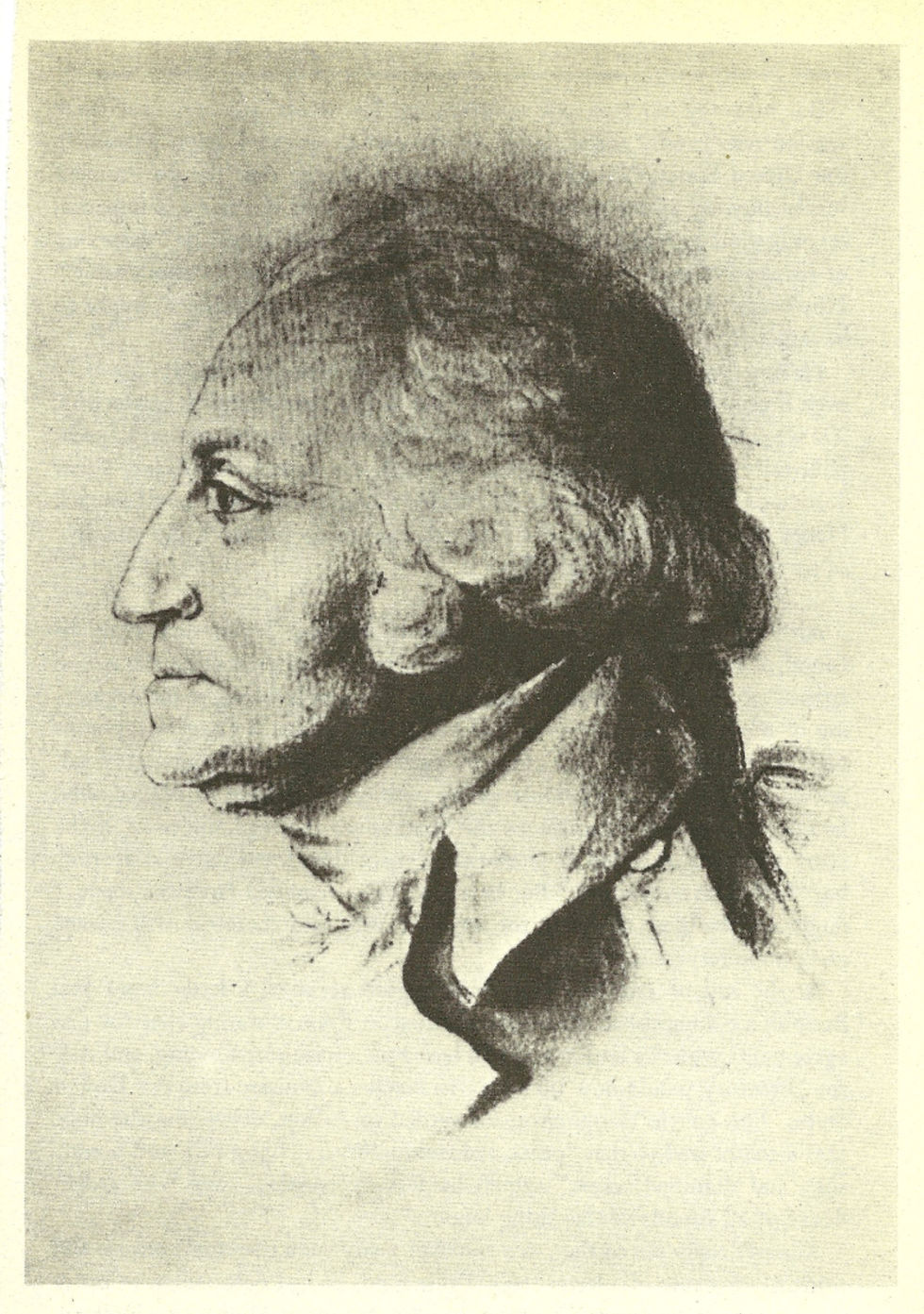

Jefferson was unique among the Founding Fathers with his interest in the arts. None of them could match his knowledge or interest in music, literature, or architecture. Great as his political writings were, Jefferson was, as one scholar put it, "first of all an artist." Work on Monticello would continue for the rest of his life. Indeed, the final touches would not be completed until 1823, three years before his death.

END -

Comments