Book review: "The Agitators: Three Friends Who Fought for Abolition and Women's Rights"

- Sep 22, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 26, 2025

by Dorothy Wickenden

Who were the agitators? They were Harriet Tubman, Martha Wright, and Frances Seward. Harriet Tubman was the most famous of the three, whose life story is well-known (indeed, her face will replace that of Andrew Jackson on the twenty-dollar bill some time in the future).

The three women comprised a unique circle of friends, whose individual efforts helped usher in what Lincoln promised in his Gettysburg Address, "A New Birth of Freedom", not just for millions of enslaved African Americans, but for women too--the right to vote, to own property, and to hold elective office. Much of the scholarship the author relied upon is drawn from the many letters of Martha Wright and Frances Seward, as well as newspaper accounts of Harriet Tubman's activity before, during, and after the Civil War. At 307 pages, the book reads more like a well-plotted novel than a dry recounting of historical people and events.

Mind you, these calls for social change came about as the result of the Second Great Awakening (of the 1830s) a nation-wide religious movement that led to the creation of several new religious denominations, including the Seventh-Day Adventists, the Church of Latter Day Saints, and Christian Science. It also resulted in a number of social reforms that included the abolition of chattel slavery, the women's suffrage movement, and the temperance movement. (Note: the First Great Awakening, of the early 1730s, led to the American Revolution).

Harriet Tubman was born into slavery on a Maryland plantation. In 1849, when she was in her early 20s, she escaped to Philadelphia (a.k.a. "The City of Brotherly Love"), that thanks to the efforts of the Quakers, had long welcomed slaves fleeing from the oppression of Southern plantations. Having found freedom, she returned to her home state as a conductor on the Underground Railroad that carried slaves to Canada--out of the long reach of slave holders seeking their return. During the Civil War she worked as a scout, spy and nurse for the Union Army.

One of the stops on the Underground Railroad, was a village in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York, named Auburn. At the time, the Finger Lakes region was the nation's hotbed of radical ideas, including abolition, temperance, and women's rights. It was in Auburn that Ms Tubman and a number of freedom seekers were given temporary refuge in the homes of Martha Wright and Frances Seward. Both women were staunch abolitionists and activists in the temperance and women's rights movement.

Giving a meal and a bed to a runaway slave was an act of courage in an era when the Fugitive Slave Acts of the 1850s was strictly enforced, and imposed harsh penalties on those who helped escapees. Strongly religious, the three women believed that God was on the side of the abolitionists, and while taking sensible precautions, did not fear being caught. Ms Wright in particular took personal satisfaction in what she was doing. On the night that the first fugitive arrived in her kitchen, she felt "a sense of satisfaction unlike any she'd ever experienced," writes the author, quoting from one of Wright's letters. A mother of seven, Martha Wright was a friend and compatriot of feminist leaders Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She also was one of the participants of the landmark Seneca Falls Convention.

The third agitator was, in the author's words, a "quieter rebel." Frances Seward got her first taste of slavery on a visit to Virginia in 1835, when she was 30. Like Abraham Lincoln before her, she was sickened by what she saw--in her case, 10 weeping black boys, ages 6 to 12, naked, roped together and overseen by a white man with a whip. The children were on their way to the auction block, where they would be sold to work in the cotton fields of the Deep South.

As the wife of William Henry Seward, governor of New York, and then Lincoln's secretary of state, she found herself in the difficult position of trying to follow her conscious without damaging her husband's political career. In keeping with her husband's wishes, she kept a low profile about her antislavery work. While her husband enjoyed the social side of Washington politics, she did not, and wasn't sad when a virtual unknown, Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, was chosen over her husband as the Republican Party's presidential nominee. Behind the scenes, however, she was a powerful and persistent advisor to her husband, pushing him to press Lincoln to emancipate the slaves.

The author does a very good job of describing life in politically-active town of Auburn in the 1840s, and in Washington D. C. prior to and during the Civil War. Best of all she breathes life into a number of historically significant characters--uncompromising abolitionist John Brown, who led the ill-fated slave-uprising at Harper's Ferry; Frederick Douglass, the gifted orator and self-taught former slave who was a neighbor and friend of the Wrights and Sewards; Harriet Beecher Stow, who wrote "Uncle Tom's Cabin"; and Lincoln, whom quoting from one of Ms. Seward's letters, describes the 16th president as "amusing and friendly, with a manner like an unassuming farmer's--not awkward & ungainly but equally removed from polish or manner." She also quotes abolitionist congressman Thaddeus Stevens, who said, "The greatest measure of the nineteenth century (the Thirteenth Amendment) was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America."

Tubman's wartime service in South Carolina is chronicled in a dramatic chapter about a military raid on plantations along the Combahee River, in which she led 750 slaves to safety.

As a sign of things to come in the postwar years, Ms. Tubman, on her way from the Fifteenth Street Church in Washington, was ordered off a segregated streetcar by a conductor.

Also chronicled is the Battle of Gettysburg, where Martha's son Willy, fought gallantly and was wounded. Another moving scene is an account of the attempt made on William Seward's life by an associate of John Wilkes Booth on the night of Lincoln's assassination. Seward's daughter, Fanny, who witnessed the knife attack, wrote in her journal afterwards: "Blood, blood, my thoughts seemed drenched in it--I seemed to breathe its sickening odor."

While violence runs through much of the narrative, so does the religious conviction of the three friends--Martha, Frances, Harriet--respectively, a Quaker, an Episcopalian, and a Methodist. Harriet Tubman went so far as to say that God wouldn't let Lincoln win the war until he had freed the slaves.

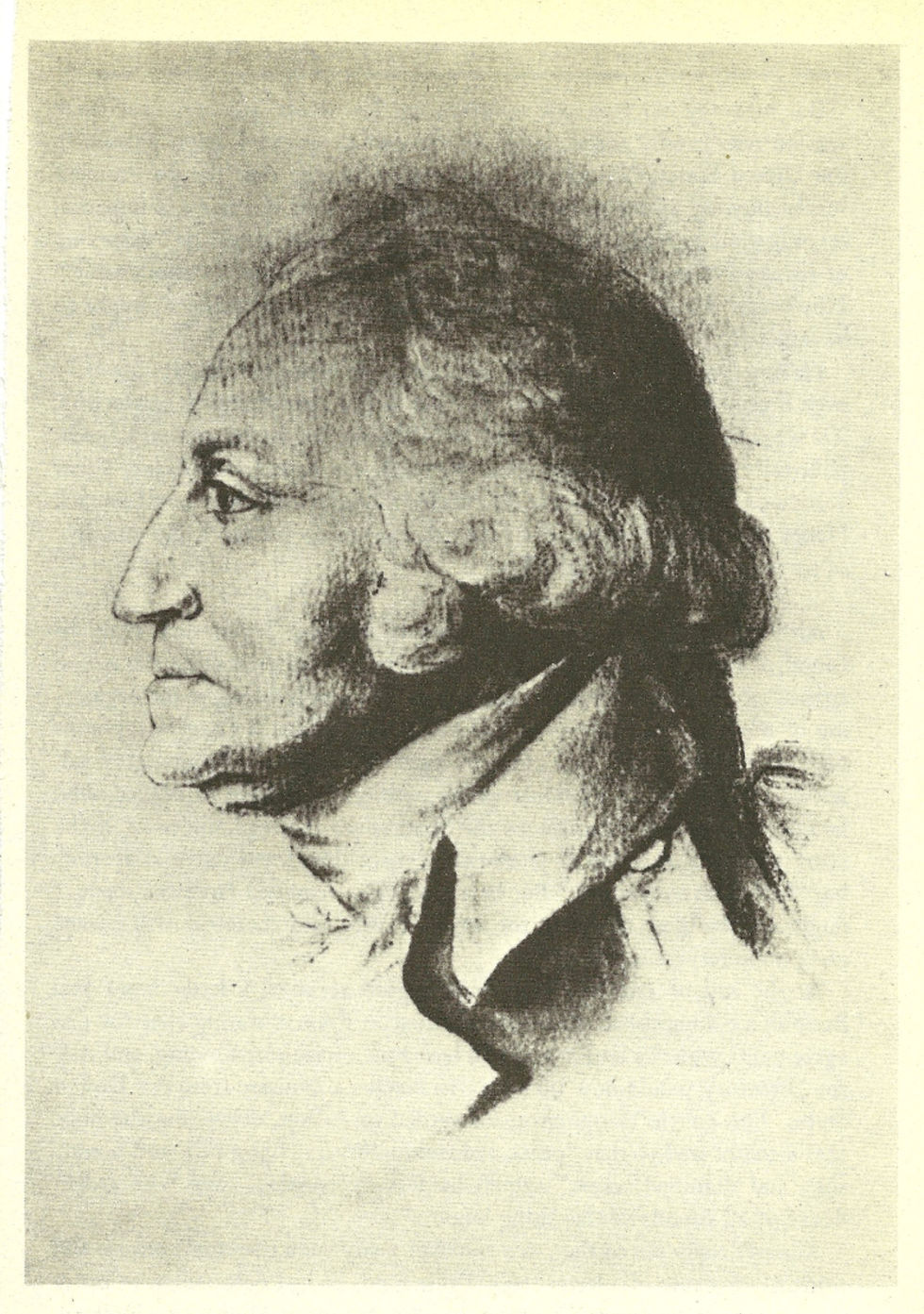

The star of the book is unquestionably Harriet Tubman, whom the author portrays as highly intelligent, determined and dignified--"a small unstoppable woman . . . unafraid of the of the slave power of the South and of the lawmakers in Washington." She lived a good, long life in service to her fellow man. After the war, she settled in Auburn, in a house the Sewards had given her. In 1869, she married Nelson Davis. In the book's closing pages is a wonderful photograph of her, taken in 1911, two years before her death at age 90. At Fort Hill Cemetery, near the Seward and Wright family plots, Ms Tubman's grave can be found under a towering Norwegian spruce. Engraved on the back of her tombstone, a tribut reads:

"To the Memory of HARRIET TUBMAN DAVIS Heroine of the Underground Railroad. Nurse and Scout in the Civil War. Born about 1820 in Maryland. Died March 10, 1913 at Auburn, N.Y. "Servant of God. Well Done."

- END -

Comments